We write to share wonder and curiosity, to illuminate universal truths and small moments, to shine light into shadows, and so that our stories can walk quietly beside readers to let them know they aren’t alone. Today, we’d like to share some of our best writing secrets — the ones that keep us going and help transform a draft from good to great.

Martha Brockenbrough, author of The Game of Love and Death and the forthcoming Unpresidented: A Biography of Donald Trump

One thing I see often in the writing of my students (and sometimes my own work) is a scene that could be made stronger with a really strong setting acting as an anchor.

We all know that lots of description can be a snooze for readers, so I’m not encouraging anyone to do that. Most definitely not!

But … we should know where we are at the start of every scene, and finding clever ways to establish that will make your writing sing.

Think about how you know where you are. Your senses tell you. Sight often dominates, so here’s a way to find fresh observations. Close your eyes right. What do you hear? What can you smell? Are you sitting or standing or in some way interacting in your environment? How is that affecting your body? Those are questions you can ask yourself about your character and their world, and you can choose the most interesting and useful ones to help your reader slide inside your character’s entire existence—head, body, and experience in that form.

And one more tip: this is sometimes something I do the day after I’ve written a scene, and when I’m trying to warm myself up for new words. I read the previous day’s work and think about how I can create more anchors and more resonance for readers. It’s always a quick way for me to get myself back into the project, and I find so much pleasure in enriching things for readers this way.

Kate Messner, author of Breakout and the Ranger in Time series

I look for small things when I write. Often, the tiniest detail is the best detail when it comes to grounding a scene in a particular time and place or bringing a huge, sweeping moment back to the personal. The tricky thing about this is that the first thing we think of as writers is almost never that perfect, small detail. We have to dig for those.

When we’re imagining a beach by a lake, we get the lapping waves and the calling seagulls right away. But when we go to a lake and listen, we also hear the two dogs barking just up the hill – one with a deep woof and one with a high-pitched yapping. We hear the far-away train and maybe the scrape-clunk-scrape of a kid sorting rocks to find just the right one to skip. These are better details.

We’ve all seen disaster scenes on television, but again, when we imagine this setting, the first details we think of – twisted beams and emergency lights – probably won’t tell the story in the best way. It’s the smaller, more specific details that make it personal – the broken eyeglasses with the red frames, the Snapple rolling down the street from an overturned bagel cart, the firefighter who’s stopped to pet a dog. The first set of details tells us there’s been a disaster; the second set makes us care.

Here’s an exercise you can try in any setting. First, just stay at your desk or wherever you are, and write a quick description of that setting. What do you think you’ll probably see, hear, feel, and smell when you get there? Now, take your notebook and go to the place. Sit down, and for five or ten minutes, just watch and feel and listen, and write down things you notice. Sniff the air, too. Everyplace has smells, and not always the ones we expect. What did you notice that wasn’t on your first list? Those might be the best details of all.

Tracey Baptiste, author of The Jumbies books and Minecraft: The Crash

The most fun thing for me about writing is cutting scenes. Knowing where to cut a scene is hard, and getting just the right ending to it is also tough, but I think about it in two ways,

- Have I shown the reader everything they need from this scene? And

- Does the ending propel them to the next one?

So the first part always involves some back and forthing. Sometimes you don’t know if you’ve given the reader everything in a scene until you get to the end of the story and realize that you didn’t set up some things earlier that they’re going to need at the end, so you have to go back and fill this into scenes you’ve already written. This is mostly easy enough to figure out once you realize that you don’t have to get the scene perfectly right the first time, and it’s TOTALLY fine to go back and re-do a scene, add or subtract, etc.

What’s more difficult is knowing how to end it in a way that makes the reader want to keep on reading. And for that, I encourage you to watch one of my favorite movies in the whole wide world, The Fifth Element.

This movie cuts scenes with razor-sharp precision and what ends one scene starts the next, and it all feels orderly, but also super exciting.

Anytime I can’t seem to get the end of a scene right, I go watch The Fifth Element to re-learn how to basically throw the reader from one scene to the next. The way the editor or director moves from one scene to the next is merciless, and I apply that strategy to the end of every scene I write. Mostly, it involves finding the connective tissue between the two scenes so that what’s dropped in one is immediately picked up in the other by someone else, in a different way, but it works like gangbusters.

And it’s super fun.

Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich, author of Two Naomis and Naomis Too

Revel in what you do well. Enjoy your writing strengths, and use them unashamedly. I think of myself as much better at character development than ‘plotting’/action, and often spend too much time as my own personal contortionist, trying too hard to PLOT THE STORY, feeling inadequate and dim. It is inevitably misery-inducing, and not very good. But when I start with and spend time with what works for me — thinking deeply about character — the story comes, and those things that I think I have to do to PLOT, do come as a more natural extension of my work. So, do you. Enjoy it. Be proud of it–congratulate yourself, even (for just a bit, don’t get all biggety. But if it were me, I *might* have a morsel of cake). And then get to work. Start from your joy, and then challenge yourself. For instance, if you start with character, keep thinking about how the fullness of your character can drive the story. If Naomi Marie is anxious to appear a high achiever and prove herself on this group project, she might take on some tasks without asking her other team members if that’s OK. Maybe she takes on too much, and that affects another activity. Maybe another group member suspects her of sabotage, and engineers revenge. Stuff can happen! If you start with action, with a bit more ‘What if?’, maybe there’s a group of kids working on a project but one has been asked to cheat in order to make a friend look impressive. What kind of character might agree to cheat, and why? How would they go about it? Who in the group might immediately be suspicious, what would they do? and WHY? Would another group member be an accomplice, and (you guessed it) WHY?

Don’t try to be a different type of writer. Start from your strengths, and let them nourish your challenges. Let your writing joys feed your struggles.

Anne Ursu, author of Breadcrumbs and the forthcoming The Lost Girl

Like Olugbemisola, I am not a person who thinks in plot. To me, books are all character–even fantasies with the most elaborate world and coolest creatures are nothing without a compelling, whole character at the center. Fantasy books are journeys–yes, external ones, but more importantly they are internal journeys. Our protagonists begin in a situation where they have some deep-seated need or wound, something so desperate and profound that only a fantasy journey can heal that wound.

Whenever I get stuck on the plot, world, antagonists, or side characters I go back to the protagonist. What is her journey really about? What does she want and what does she really need? How can I design the rest of the story to challenge her and change her so that need is met by the end of the book?

When writers I work with are having trouble with their books I often have then write a journal entry from the protagonist’s point of view from the night before the book starts, where the protagonist confides all of their feelings and desires. Maybe the root of these desires runs far deeper than they know; after all they haven’t had a fantasy journey yet. But out of this exercise, I hope, comes a sense of what the gravity of the book is, the thing every other element should revolve around.

Laurel Snyder, author of Bigger Than a Breadbox and Orphan Island

As a teacher, I probably talk more about “default writing” than anything else.

Of course, we all have defaults, and occasionally, they can be useful. But learning to write well means learning to interrogate our defaults, to question their value in each instance. This means that we all need to know how to identify our defaults on the page, and consider other (better?) options.

Like the man said, KNOW THYSELF!

An example: I’ll confess that often, in my books, I default to BLINKING. Characters who are confused or upset or stunned or happy will BLINK, as a way of expressing that there’s a lot going on inside them. Now, this is fine once in a while, but it’s kind of a cheap trick, a manipulation, and I certainly don’t want to rely on it too often. So now that I recognize my BLINKING default, I look out for it. In fact, at the end of each draft, I do a search for the word “blink” and then replace that word/moment with something else, in each case.

An easy exercise that can help with this is something I call the HIGHLIGHTER TRICK. Simply take a printed draft of your work, and a highlighter. Now, read the manuscript backwards, sentence by sentence, beginning at the very end. You aren’t reading for content, so you don’t want to read forward, and get caught up in the narrative. You want to slow down and read each line on its own, as a discrete sentence. Paying attention to the words themselves, rather than the story. And each time you see something familiar—a word or phrase or sound or gesture that you know you’ve used in the past—highlight it. Then, once you’re done reading the whole thing with your highlighter, go back through and treat the story like a Mad Libs, replacing each highlighted item with something else.

One last note: when you find yourself absolutely resisting a specific change, that’s fine! Leave the highlighted section as is. Because sometimes in life, your default is the exact right instinct. The point isn’t that you should never use it. Rather, that you should CHOOSE it, each time, the way you should choose everything carefully.

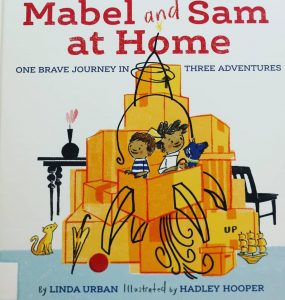

Linda Urban, author of Road Trip with Max and his Mom and Mabel and Sam at Home

The best way to become a better writer is to read more.

You knew someone was going to say it, didn’t you? Next to writing a lot, reading a lot is the most commonly dispensed advice there is. Because it is very good advice.

Here’s what gets said less often, but is just as important: Read Aloud.

So much of writing is about the sound of things — the way words bounce or clash, the rhythm of sentences, the pitch of paragraphs, the hush of the rests between them. I realized recently that some of my best, most joyful writing has happened during times when I was also actively engaged in reading aloud to my children. It gets in your head, that sound, like an earworm tune you’re not even aware of until you’re singing along with it. Read aloud to write work worthy of reading aloud.

And then, do that. Read your own work aloud.

How does it sound? Are there consonants clacking when you intended a soothing swish? Does a languid pool of description slow down what ought to be a high speed hydroplane race? Have you spiraled madly round a manic moment only to peter slowly out? Again? Really? Fine.

Read it aloud.

Find the beat.

Make a change.

Read it aloud, repeat. Or re-beat. Until, finally, it sings.

Do you have a favorite writing secret to add? Please feel free to share in a comment. We hope you have a great National Day on Writing and a year full of wonderful stories!

Thanks for collecting all this tips in one place. What a great resource.

These are fun and fascinating tips! I was at an author’s panel last weekend, and two of the authors said they take quizzes as their characters. Meyers Briggs, Hogwarts House, what type of bagel are you–all the quizzes. It helps them to get a good sense of who their characters are and therefore make sure the character reacts as themself, not as the author would.

Your thoughts and suggestions are great! I am going to use them to help guide my students who struggle with revising. My class is planning their next story to write this week. I definitely will tell them these ideas came from you by referring to this blog post. So helpful! Thanks again!

When I started writing, I spent a lot of time figuring out the WHATs of my character. What does she wear? What does she have for breakfast?

But no matter how many of those I listed, the characters didn’t really come alive.

I finally learned that for every WHAT, I needed a WHY. “She wears old torn jeans” doesn’t really tell me anything about the character. “She wears old torn jeans because she’s paranoid about being kidnapped and she doesn’t want anyone to know she’s a billionaire” suddenly opens up a world of possibilities.

And now that I know that WHY, I know HOW she’ll behave in whatever situation I throw her in

Thank you for these seven insights – I feel fortunate to have mentors like you all.