Earlier this week, I wrote a blog post called “Remember Who We Serve: Some Thoughts on Book Selection and Omission,” which you can read here. I explained that after I was disinvited from a school visit in Vermont last week, another librarian from a different state contacted me to let me know that she loved my books but had removed THE SEVENTH WISH from her library’s order list because of its content.

Earlier this week, I wrote a blog post called “Remember Who We Serve: Some Thoughts on Book Selection and Omission,” which you can read here. I explained that after I was disinvited from a school visit in Vermont last week, another librarian from a different state contacted me to let me know that she loved my books but had removed THE SEVENTH WISH from her library’s order list because of its content.

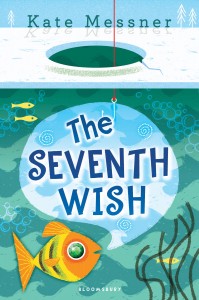

THE SEVENTH WISH earned a starred review from Kirkus, which called it “Hopeful, empathetic, and unusually enlightening.” The book is about lots of things – Irish dancing, ice fishing, magic, entomophagy, flour babies, and friendship. It’s also about the shattering effect our country’s opioid epidemic has on families.

That librarian who removed the book from her order list responded to my blog post with a comment that made it clear she was upset, so I emailed and asked if she’d be open to talking more about this issue. She said yes, and we had a great phone conversation this past Saturday. I learned that she does indeed see the other side of the argument as well, but she still thinks kids’ innocence should be preserved longer by limiting access to some topics. She’s also under pressure from parents in her community to limit the kinds of books in her library. The bottom line is, she feels like she can’t give elementary students access to a book like THE SEVENTH WISH without risking her job.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how we can all do a better job supporting librarians and teachers who want to provide kids more access to books but are worried about pushback, so I proposed that this librarian and I start a conversation and invite others to participate in that discussion, too. She and I have profound disagreements about what kinds of books belong in a K-5 library, but that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be able to disagree respectfully, listen to one another, and try to brainstorm solutions. We’ve been doing that for a few days now, writing back and forth via email, with the understanding that she remain anonymous. She’s worried about repercussions from her school for speaking out, and about personal attacks due to her views. I’m honoring that wish so that we’re able to share that conversation with you. So as you read the conversation, know that K is me, and L is the librarian with whom I’ve been sharing ideas this week. It’s a long conversation, but I wanted to share it all in a single blog post so that people who read it aren’t just getting bits and pieces. Here’s what we’ve been talking about…

K: First of all, thanks for agreeing to have this open conversation. I’m a little nervous but also excited to be talking openly about our disagreements about elementary libraries, book selection, and access for students. I know that many K-5 librarians carry a wide range of books that we might consider “older” titles, mostly appropriate for 4th and 5th graders, while others, like you, are a lot more cautious out of concern that a very young student might bring home a book that’s meant for the older elementary readers. I know that you haven’t read THE SEVENTH WISH just yet (and I’m still hoping that will make a difference) but I know from your earlier email that you removed it from your library’s book order list when you learned that one of its themes was the effect our country’s heroin epidemic has on families, especially younger siblings. Could you talk a little about your immediate reaction to learning that and why it made you re-think your book order, even though my other books are popular in your library?

L: Thank you Kate for starting this discussion. I think it’s important for people to read and respect both sides of the issue, and I am very open to hearing what other educators have to say. As a parent of young children, I admit I am having a lot of trouble separating my personal and professional opinion on this one.

As I was reading about The Seventh Wish I noticed that it is marketed as a middle grade book. Where I live, middle grade is 6th – 8th. I will be the first one to donate a copy to our middle school library, but where I keep getting stuck is pushing a middle grade book into an elementary school library. Ranger in Time was the best seller at our most recent book fair so that gives you an idea of where my students are as far as their reading level both academically and emotionally.

During our discussion, you mentioned one of her fears was that not having your new book on the shelf would be the same as saying that the life of a child with addiction in their family is inappropriate. I completely disagree. I don’t feel that way in the slightest. My heart breaks for children struggling with addiction in any way but my feelings are simply leaning in favor of keeping our youngest students (without this struggle) from growing up too quickly. How do I get the book to students who need it while protecting other kids who might suffer from reading it?

I have been teaching for almost 20 years, and I have had the privilege of teaching different levels. This has been wonderful for me as an educator as I’ve been able to see all ages and levels and get a fairly decent idea of how children at all age ranges react to and handle a variety of topics. Something that has always amazed me is the huge difference between fourth grade and sixth grade. The changes within those two years are incredible. The growth and maturity that take place really turns them into totally different students. As their bodies change, so do their minds about the opposite sex. Girls are no longer icky and most of the boys grow taller than me! It’s really fun to watch them change and mature. It’s also much easier to have well thought out conversations about really important topics. I find that in fourth grade conversations about tough topics need to begin, but I personally feel like there needs to be a line. I can control my ten-year-old and I can control what happens in my house, but I can’t speak for every parent out there.

Let me start by describing that usually happens in the school library vs. the public library. When I take my son to the public library, I’ll bring him there to look around and when we go to check out, I look and see what books he’s bringing home before he starts to read them. When he gets a book from the school library, he usually starts reading it before I even see it. The same goes for where I work. Students get their books and most start reading it right way before class is even over. Most often, a book with mature content doesn’t even make it past the eyes of their parents first, if at all. Years ago I let an older student check out Twilight and I had a parent incredibly angry at me because she had told her daughter she didn’t want her to read it. How was I supposed to know? That was between her and her daughter but of course that led to a bigger discussion about having something like that on the shelf.

Also, let’s not forget that all it takes is one parent to get angry enough to get my job taken away. I don’t know that any book takes precedence over a career I love and a job I need. So that is one part of my fear here. Students are checking out books with mine being the only supervision, and I can’t possibly know every parents wishes and concerns. That’s why I try to have something that just about any child could pick up off the shelf and the content would be O.K. Every once in a while a second-grader will sneak by me with a book where I think the reading level is too difficult but luckily the content is still benign. It is my ultimate responsibility to balance student wishes and parent concerns.

One of the biggest concerns throughout our fourth and fifth grade population is extreme anxiety. Disorders such as panic attacks, anxiety and even depression are on the rise for our youngest students, and I feel like it’s only gotten worse as the years go on. These students represent a much greater population in my area than those affected by drug abuse. I don’t know if it’s more technology or more television or what, but so many of our students’ greatest problems revolve around constant worries. Having a fourth-grade child puts me in direct contact with many other fourth-grade moms and we have the same discussions over and over. Why are our children up at night crying and worrying about things matter how safe we try to keep them? They worry about getting in trouble, things on the news, something happening to their loved ones, not making the team, or someone being mean to them. My own son’s list of fears always amazes me. He was reading Stuart Gibbs’ Spaced Out the other day and had to stop because he got scared of a giant robot arm on the moon. I have friends whose kids can’t watch the Avengers because it’s too scary, and I also know several children who read The Hunger Games without their parents’ knowledge and cried with nightmares for several days. My closest friend had to stop buying I Survived books for her son because he became terrified that a natural disaster was going to hit at any minute. Who am I to say what will or won’t upset someone’s child? It’s a huge burden that I take very seriously. A fourth grader is very fragile and their minds are just starting to open to the scary things in the world. They don’t quite have the maturity to know how to process it and deal with it. Thankfully I don’t live in a community where young kids are put in dangerous situations on a daily basis.

I know there are many places where this is different and perhaps that would change my thoughts dramatically. Drugs are a very scary thing and 4th and 5th grade is the point they should absolutely start to learn the dangers and saying no, but this is where the conversation should just begin to start. Our D.A.R.E. program starts in 5th grade led by a team of educated officers armed with the training and resources to thoughtfully present material and answer questions. Parents should continue the conversation if they feel it is right for their child. I don’t think that most fourth-graders, at least in my community, are ready to hear about heroin addiction and overdose on their own through a fiction book without parent guidance.

Why add one more fear to his or her brain that isn’t there? For what purpose? Yesterday you spoke about a student learning empathy for a child who is going through drug addiction and their family. Of course that would be extremely important, but what if it’s not something that is happening in their life right now? If there was an overdose death in the community that affected our children then I think The Seventh Wish should be pulled out immediately, and I’m thankful it’s there. I guess I keep getting stuck on the idea of putting a new fear in an already fear-filled brain. What age is O.K? 10, 9, 8 years old?

Yesterday, after my discussion with you, I carefully opened this topic with my son. We’ve talked about drugs before and peer pressure and the dangers, but we haven’t delved into heavy specifics. We were driving to the store and he asked me why I have been on my computer so much. I told him about what was going on with your book, and we started to have a little bit of a conversation about the dangers of drugs. He said, “I know drugs are bad. I would never do that. I don’t want to talk about it. I just want to get home so I can play in the sprinkler with Max” (his brother). I wondered if maybe I should have him read this book but then I have to ask, why? He just wants to play in the sprinkler with his brother. He doesn’t know anyone addicted to drugs and that’s luckily not part of his life for now. Why do I want to give him something to fear? I know the types is questions I will get- Why are people doing drugs? What is heroin? Where do you get it? What does it look like? How does somebody die? What happens to their bodies? Could I take drugs by accident? What if someone makes me do it? I’d be fueling anxiety for weeks. One thing we have certainly learned about a 10-year-old is that when you tell them something and you think they’re fine, the minute they are alone their brains work it out over and over again and they think about it, they analyze it, and they pick it apart trying to understand it.

I also shared your blog with several of my friends, some elementary school teachers, and parents on the baseball field yesterday. They all vehemently agreed with me that while a book like that would be important, they would not want it in the elementary school library. Parents want to feel like they can send their child to school and they will come home with something safe. Again this is the predominant thought in my community, and I am well aware it would be different for other towns. I’m not a book burner, I’m not an extreme conservative and I don’t support banning books at appropriate age levels. If a child wants to read about heroin with their parent’s permission then that’s completely fine with me. If that’s what their family wants to discuss then they should buy all means do it, but when it is my responsibility to assure parents that what I have on my shelves will keep their 10-year-old as anxiety free as I can, then these are the kinds of decisions I need to make.

I’ve read some of the comments on the blog where people are crying censorship and that I don’t know what I’m talking about. Maybe there are some liberal communities out there that totally embrace telling their children every possible bad thing that could happen to them in their life, but once that innocence bubble is popped they can never unlearn those things or remove those images. I want some more hours of sprinklers, mud pies, and running around with light sabers. I know that it is a privilege that my son can have that kind of life, and I am well aware that there are communities where children are desperate for a book about finding their way through family addiction. This book would be a tremendous comfort for them and their friends. Ultimately I think it’s each librarian’s prerogative to look at the demographic and what their greatest community need might be. I just don’t see it here. While I’m certain there are families dealing with drugs, I believe that to be a very small minority in my particular town compared to the children suffering from anxiety. The students of my district and my own kids will have access to this book for sure in sixth grade. Can’t we let the fourth and fifth graders be free just a little longer?

K: I appreciate your willingness to engage in this conversation so thoughtfully. I feel like I addressed my thoughts on a lot of this in my earlier blog post that prompted this conversation, “Remember Who We Serve: Thoughts on book selection and omission,” so I’ll link to that for anyone who hasn’t seen it and just add a few more thoughts and questions to our conversation here.

I think there’s a vast difference between a middle grade novel like THE SEVENTH WISH, which industry reviews like Kirkus and SLJ recommend for grades four and up and a book intended for teens, like THE HUNGER GAMES. But the books we’re talking about are intended for upper elementary readers. Even though they tackle tough subject matter, they do it in an age appropriate way.

I understand your concerns about kids and anxiety but wonder how you handle other scary topics in your school library.

Do you carry the I Survived books, for example, since they are intended for your age group but can be scary for kids who worry about natural disasters?

Do you have any sad novels that deal with the death of a parent or other loved one? What about books where a family member has heart disease or cancer?

I’m also curious how your library deals with books on other topics that can be controversial in some communities. Alex Gino’s award winning middle grade novel GEORGE, for example, is left out of some school libraries because it’s about a transgender fourth grader. What did you decide about that title in your school?

Mostly, I’m wondering where you think we should draw that line. Is it our job as librarians and educators to protect kids from any books and ideas that might upset them? It seems to me that if we removed every potentially anxiety provoking book from the library, we’d be left with a mighty small collection that neglected the needs of many readers.

I found your reflection on the privilege of having a protected community to be a thoughtful one. “I know that it is a privilege that my son can have that kind of life, and I am well aware that there are communities where children are desperate for a book about finding their way through family addiction.” I agree with you on this, but I’d bet that even in your safe-feeling community, there are kids struggling and wondering and looking for a sign that they’re not alone. Those may very well not be the kids whose parents you were able to talk with on the baseball field or in the faculty room. They’re also kids who can’t always get to a public library with a family member. When I taught middle school, I know that for most of my students – more than half – the only books they encountered were the books our school librarian and I put in their hands and recommended.

And this question… “Can’t we let the fourth and fifth graders be free just a little longer?” For me…as a parent, the answer to this question is absolutely yes. But as librarians, as teachers, as educators charged with providing access to books for all the kids – not just our own – I feel like our responsibilities are different. How can we better balance those two concerns – respecting parents’ rights to choose books for their own kids and making sure all our students have access to the books they want to read and the books they need?

L: The funny thing about this debate is that I agree with so many of your points. How do we responsibly choose books that will educate our students and add to the quality of their lives? I wish I had a perfect answer. This is something I struggle with every year. I think when I was younger, before I had my own kids and when I was willing to take on the world, I would have allowed almost anything of value into my classroom. Now, after years of teaching experience, multiple parent conversations, and becoming a mom myself, I’m just more cautious. These days I think about the parents and kids I serve, follow my instincts (right or wrong), and try to choose books that will help more than harm. I weigh the potential backlash of each book and when a book’s topic is something that I am struggling with putting out there, then I know it’s not right for my library.

I wish I had a more formulaic approach that it being simply a feeling that I have. But you are right- who assigned me judge and jury? Why is my opinion right or wrong? You write about it being our responsibility as educators to expose them to a broad range of topics. I disagree. On my first day of my first education class, the professor had written “In Loco Parentis” on the board. It was the first thing he taught us wide-eyed newbies. This Latin term means “in place of the parents” and in my classroom I try my best to take on the responsibility of parents in their absence. Do I often take the “better safe than sorry” approach? You betcha- just like I hope my kids’ teachers do. Also when I taught middle school these decisions didn’t weigh on me as heavily as they do with the younger grades.

You are spot on that we can’t possible remove every book with anxiety inducing topics. Death, cancer, autism, and divorce are all issues in books I have on my shelves. My star reader actually came to me one day a few weeks ago and asked if I had anything that “wasn’t so sad.” Since she was an advanced student, I realized I had been recommending many challenging (and sad) books. I felt terrible and directed her to DORK DIARIES. This poor child hadn’t laughed at a book in weeks and it was bothering her. So where do I draw the line? I suppose I try to determine if the material goes further than the MAJORITY might be emotionally ready for. Does that exclude some children who could really use the book? Probably, but to help a few do I sacrifice many? I SURVIVED is a high interest series that boys, especially my reluctant readers, flock to. I know there are some students who find these books scary, but I think a discussion about something that happened in history might be more easily handled than heroin addiction. I just hope that a child who might be scared by the first one they read won’t keep coming back for more in the series. I also know that more students are O.K. with these books than not O.K.

I had a feeling you would ask me about GEORGE. When my son asked me last year what it meant to be gay I told him all about people having the right to love whomever they want. I even told him about the Supreme Court’s decision and reiterated that our family loves everyone no matter what their sexual orientation might be. He was fine with it and ran off to jump on the trampoline. Should I have called him back and said, “Now I would love for you to read GEORGE.”? He was great with the baby steps into the conversation of homosexuality and I didn’t feel a need to expand or confuse him. As he gets older and has more questions, I’ll put that book in his hands, but not now. I also know that if that book was displayed in his library he would have picked it up solely because the cover is appealing and he thinks George is a funny name. I’m glad they don’t have it there. I’m not ready for him to know more and if I’m not ready, the parents I work for certainly aren’t ready. Last year when DRAMA by Raina Telgemeir was all the rage, I caught students huddling in the corner and snickering at the part in the book where the boys reveals he likes other boys. It was very innocent and not mean spirited, but it was also a clear indicator that they are not emotionally ready for something delving deeper into the topic.

So again it comes down to what I can do to get these books into the hands of the right students and not the wrong ones. You are correct when you say that children in need of these books might not have access to the public library or parents willing to have thoughtful discussions. Maybe I get the books and send out a notice to parents letting them know they are here if they need them. Perhaps I give a set to the guidance counselor who knows more than me who could be helped and leave it to her to decide who reads them. Maybe I invite the author to talk to the parents about the book and let the parents decide. Am I taking away a teachable movement for other kids? Yes I am, but under the umbrella of “In Loco Parentis” is where I feel comfortable.

K: I understand your desire to parcel out information to your questioning son. We did that with both our kids when we started talking with them about things like sex – we’d answer the questions and offer more information as long as they seemed interested. When they left to play Legos or jump on the trampoline, we’d let it go and pick up the conversation another day. But I still feel like that’s a parenting issue rather than a school library one. You know your son. You don’t know every challenge or concern or question your students might be dealing with on any given day, even when you talk with a selection of their parents at your son’s baseball game. Not all the families are represented there. But I believe all of those kids should have the opportunity to see themselves in books in a school library – maybe especially kids whose lives are different from your son’s.

The suicide rate for transgender youth is heartbreaking. 41% of transgender people will attempt suicide in their lives, compared to 4.6 per cent of the general population, according to this study from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the Williams Institute. Kids struggling with this need to feel less alone, and their classmates need to have empathy. Books are such a valuable way to do that. Instead of thinking, “Oh, that transgender kid is so WEIRD!” when a classmate is struggling, a reader might think, “Oh! I know somebody like that, because I met Melissa, the main character from GEORGE.” While I can’t back this up with a research study, I’d be willing to bet that children who have access to more diverse books are kinder and less likely to engage in bullying.

Might this book be challenged or questioned by a parent? Maybe, depending on where you live. But sometimes, I think our fears over this are bigger than the reality. The Maine teachers who just read THE SEVENTH WISH aloud with all of their school’s 5th and 6th graders sent home a letter beforehand, explaining that the book was about a family affected by heroin addiction. Do you know how many concerned parents wrote back to complain about the topic? Not a single one. But even when those phone calls do come – and I know how difficult they can be – I’d argue that kids’ lives and kinder communities are worth the fight.

After I read your latest email this morning, I revisited the American Library Association Code of Ethics. Here’s what your professional organization has to say:

—————————————

Since 1939, ALA has recognized the importance of codifying and making known to the public and the profession the ethical principles that guide librarians. The Code of Ethics will be seventy years old in 2009 and has evolved into a statement of eight principles that embody the ethical responsibilities of the profession. The Code was last revised in January 2008.

The ALA Code of Ethics guides school librarians to:

- Provide the highest level of service • Resist all efforts to censor library resources

- Respect intellectual property rights

- Treat coworkers with respect, fairness, and good faith

- Distinguish between personal conviction and professional duties

- Not allow personal beliefs to interfere with provision of access to information

—————————————

I understand that this is all easier said than done when one lives in a more conservative community. But I do strongly believe there are kids at your school who would benefit from a wider selection of books, even as the parents of other kids would like to keep those books unavailable to their own readers. Where does that leave a librarian, given the responsibilities ALA outlines above?

Do you know if your school district has an official selection policy for school libraries? Most do, and I know that many librarians use that as backup when they’re working to ensure kids have access to books. It can help a lot when one is facing challenges from parents or administrators.

L: I will certainly look more thoroughly into official policies about book selection. You are correct though – I suppose my biggest struggle is separating myself and my son from the parents and children where I work. Every night I look at him and imagine my students because my home looks similar to others here in our suburban town. That being said, there are books I put out that I know he would find worrisome but I do it any way because I can’t and don’t always go by him. Maybe I’m too close to this age group. Perhaps the 30+ people I asked this weekend are too close to this age group and community, but I this is where I work and live. This is the demographic I serve. I am sure there are communities where your book isn’t being marketed because the need might not be as great.

You ask me “What about the one student whose life will change because of these books?” I cannot risk the emotional well begin of K-3rd graders and take the privilege of those discussions away from their parents. I am very open to finding ways to getting your book and its message to my students and families that want to start the discussion, but I don’t feel comfortable deciding it for them. The library is open to all students ages 5-11 and our books need to reflect and respect those ages. Perhaps I can suggest your book for our 5th grade classroom library where I know no other younger student will have open access to it. Maybe I need to take some formal surveys and speak to administration to clarify their position and I am totally willing to do that. I also want to be clear that no parent or administrator has ever asked me to remove or limit a book in my current school (I’ve had different experiences in the past). Everything I write in this discussion is my opinion and does not reflect any one else in my district.

I am getting nervous to publish this conversation because what I am reading in the comments makes me sound like I am some unreasonable book banning conservative and I’m not. People are pulling out tiny excerpts from what I have written and painting me in a light I am not at all comfortable with. I am simply a teacher that looks at her entire population and makes the best decision I can in everyone’s best interest. Everything I put into this library could possibly be read by any K-5 student and I take that responsibility very seriously. When I read the comments on your blog today from the two moms who are grateful for my decisions then I feel validated. Your blog is going to contain your fans that most certainly agree with you. The majority of teachers and parents might agree with me but they aren’t going to be out there writing about it.

Again, I really want to clarify that your book should be out there for students to read. 100% it should be on the shelf in upper grades, but when my littlest ones who tear through RANGER IN TIME automatically go to the stacks for the new Messner, what do I do? Do I let them take it without saying a word that it’s not going to be what they think? They will want it simply because you are the author without even bothering to read the back. Do I ask for a note from home to read the book with the cute goldfish on the cover?

One of the comments on your blog (it was pretty mean) asked who do I think I am to decide what kids should be exposed to. I agree- who am I to decide what kids should be exposed to? Who am I to tell a parent that I don’t care what they want their child to know? Should I say that I’m going to put out everything and if they don’t like it too bad? There MUST be room for taking into account what a parent wants for their child’s school library where they aren’t there to help make the decisions. They count on me to make good choices. That’s why I try to rely on my parental instincts, but I’m open to delving deeper into trying to find out exactly what my parents expect and want.

Good luck on your book tour. I look forward to new ideas you gather about this conversation.

——————————–

That’s where we left our conversation, and we’d love it if you’d join us at this point. I suspect this librarian was correct in assuming that many of my blog readers agree with my passionate views on providing kids access to books. So for her, agreeing to a conversation here is a little like a Yankees fan agreeing to stand up and share ideas about their baseball team’s merit in the middle of a crowded Fenway Park. I’d love it if we could all keep that in mind. I would love for this conversation to continue in the spirited and passionate but also respectful tone that we’ve managed so far.

Most of all, I’d love to hear from other K-5 and K-6 librarians who might be able to help this librarian with her concerns. How do you manage these issues in your own library? How can she feel safer about putting books like THE SEVENTH WISH on library shelves so that readers who need them have access?

Please know that comments from first-time commenters have to be moderated before they appear. This feature is turned on because as a woman who shares opinions, I sometimes get random, hateful, misogynistic comments left on my educational blog posts, and I do not allow those comments to appear. I’m on book tour right now, so it may take a little while for your comment to be approved so that it appears, so please be patient with me. I promise I’ll check in whenever I can.

Finally, I’d appreciate it if comments left on this post are both respectful and productive. Feel free to disagree with both of us, but please do that without engaging in personal attacks. I’d love for this conversation to be one where both sides feel heard. More than anything else, I’d like to come up with some creative solutions that increase kids’ access to the books they need. I will be using some of the comments in a future blog post to continue this conversation. Thanks in advance for joining the conversation in that spirit.

I am thinking of my 5th grade students here along with my eighth grade students. I find that both grades are on the “cusp” of age categories for books, and have a hard time finding books they like. There are many 8th graders who either don’t like or aren’t allowed to read the adult content in YA, but kids read up, and most MG characters are younger than them, so they feel like there is ~nothing~ to read. I feel the opposite happens in 5th grade. Most of those students won’t be interested in the picture books selected for the Kinder crowd. I hate it when not having the right books turns kids off reading, it’s really sad. Such a wide age range to account for is certainly a balancing act and I applaud elementary librarians for being able to walk that line – keeping the older kids engaged and interested in reading, while also providing a safe space for the younger kids. I don’t see an easy answer here. I do encourage the librarian to read Seventh Wish, even if she ends up not stocking it in her library. Good luck to both of you, thank you for having this conversation

As a parent, I don’t want my 7-year-old (who is an extremely strong reader who dallies in the 6-8 section) to run across a book centered around a topic I find age-inappropriate. Perhaps a good compromise would be to have these books available to students who ask for them? Or have teachers recommend books to students who might benefit from more controversial subject matter? There has to be some middle ground here between outright censorship and putting a book in my child’s hands that she’s not ready for.

As a teacher, I see that as the parent’s job. I serve over 100 students and at the beginning of the year I send home a letter explaining to parents that my classroom library serves all of my classes. As a result, the themes, topics, etc range from middle grade to adult. I ask parents to talk to their kids about what they are reading, to keep abreast of what they take home. If they are uncomfortable with a choice they should tell the child and then let me know so that I can help them find another book. This way mom and dad are involved in their child’s reading life and I am not censoring an entire population for just a handful of parents. I’ve found this to be a good compromise.

I imagine it’s even more difficult for librarians, as they may serve hundreds of students and often have volunteers and aides helping children choose books. They can’t possibly know every family’s preference/situation!

I’d like to thank both of you for mirroring what a thoughtful, honest, and respectful conversation about a differing of opinions looks like. Particularly this week, as we see the tragic results of carrying hate, and in the midst of an election with so much nasty name-calling. I’m guessing we can each agree that ALL of our kids need to see examples like this of open-minded and genuine discussions on divisive topics. Adults “adulting”–it’s so refreshing!!

Thank you for starting this conversation, and for modeling civility and respect in a difficult conversation. I think you are both brave and thoughtful women.

For five years I worked in a school that served students in grades 4-6, including a number of self-contained special ed and academically advanced classes. It’s certainly a balancing act, but I’ve always erred (as a teacher) on the side of more is better. Like you, Kate, I send a letter home at the beginning of the year explaining that my classroom library serves all students that I teach so that means that my books serve a population, not a single student or family. Actually, you inspired my letter, Kate! I had 5th and 6th graders tell me that their older friends offered them pot. I have students who just a year later were arrested for selling prescription drugs in the middle school locker room. I had students with alcoholic parents, parents who died on 9/11, parents who were not present or were too present. We serve all of those kids. As an author once said (I wish I could remember who!), kids are living lives every day that we would be horrified by. It’s our job to do what we can to support and help them. Books are an easy way to do that.

I had 5th and 6th graders tell me that their older friends offered them pot. I have students who just a year later were arrested for selling prescription drugs in the middle school locker room. I had students with alcoholic parents, parents who died on 9/11, parents who were not present or were too present. We serve all of those kids. As an author once said (I wish I could remember who!), kids are living lives every day that we would be horrified by. It’s our job to do what we can to support and help them. Books are an easy way to do that.

I wonder how this librarian and teachers who feel the same way handle historical fiction? Here in NJ we have a Holocaust curriculum so in elementary school students read novels about the Holocaust in ELA every year. Was this difficult? Absolutely. But while some students struggled with the events depicted in books like Number the Stars, Devil’s Arithmetic, and The Upstairs Room others had family members who lived through events they read about. Do we treat historical horrors differently than current events in books? If so, why?

Edited to add- I now teach 9th and 12th graders and send the same message home. My students range from very sheltered 13 year olds to very streetwise 18 year olds. My library ranges from middle grade to adult for this reason.

As an elementary librarian and mother, this topic is one I struggle with. I know my district policy of book selection and work to follow it. I am very liberal as a parent; very open to what my children bring home. In fact, I often suggest books with themes that are controversial for them to read. I believe reading about an issue builds tolerance and life experiences that perhaps they\’ll be better equipped to deal with in real life. As a librarian, I know I cannot push my personal liberal views onto my patrons. I follow the selection policies of my district, but also know of many conservative views in my community. I strive for age appropriate in my library by segregating my books. I have an Everybody section and a Fiction section. In the Fiction section, students 2nd grade and younger have to have parent permission. Once they hit 3rd grade we discuss book age appropriateness (I relate it to video game ratings.) and help my younger readers to understand why I might not allow for them to check out some books without parent permission. My first year as librarian, I purchased My Mothers\’ House by Patricia Polacco. Love this book. It was challenged by an ultra conservative parent, taken straight to the superintendent and I was called \”an evil, evil woman\” for allowing this kind of book in my library. There is board policy on book challenges and our superintendent didn\’t want to follow them because he didn\’t want media involved. The book was removed from circulation and placed in the counselor\’s office. I was so new and didn\’t know what to do, not wanting to loose my job, I followed what this superintendent asked. Since then I have better equipped myself with board policy, selection policy and ALA guidelines. I work to defuse parent challenges, and have formed a committee of teachers to help me when I face book challenges. It is scary… facing book challenges, but follow book selection policy, ALA guidelines and there shouldn\’t be issue.

As I said on twitter, reading her initial comments greatly upset me as the child of a drug addict, and I’m really glad I got to hear more from this librarian and learn more about where she’s coming from. No matter what, I respect her need to consider her job first. I also respect that she knows her community. But I stand by the idea that there is a possibility that she doesn’t know her community as well as she thinks she does. My teachers did not know my father was a drug addict. They did not know he was ever in jail. My mom always handled all the school stuff and so no one knew the difference. So that’s where I’m struggling–what if there’s a girl like me in this librarian’s school? Who is serving her? And why do we sometimes privilege preserving the innocence of some kids over dealing with the realities of others? To me, it sends a message that the other kids are already damaged, so we should focus on keeping the other kids perfect. I KNOW that is not what this librarian thinks, but that was my first feeling.

First of all, thank you both for this discussion and the respect you have for each other.

I’d like to respond to the discussion of anxiety and worry for kids. I understand the desire to limit new things for kids to worry about and respect that there are things that — if not approached in an age appropriate way — might increase anxiety. But I’ve also discovered that most often worry diminishes when we have more information, not less.

May I share one of my favorite Mister Rogers songs? Here:

I Like To Be Told

Written by Fred Rogers | © 1968, Fred M. Rogers

I like to be told

When you’re going away,

When you’re going to come back,

And how long you’ll stay,

How long you will stay,

I like to be told.

I like to be told

If it’s going to hurt,

If it’s going to be hard,

If it’s not going to hurt.

I like to be told.

I like to be told.

It helps me to get ready for all those things,

All those things that are new.

I trust you more and more

Each time that I’m

Finding those things to be true.

I like to be told

‘Cause I’m trying to grow,

‘Cause I’m trying to learn

And I’m trying to know.

I like to be told.

I like to be told.

Mister Rogers may have written this song for his preschool audience, but I think that it applies to older audiences, too, especially the part about trusting those who tell us things that we most want and need to know, even if it might hurt. When we make books about difficult subjects available to kids, we are helping them not only to think about and process things that might scare them, we are saying that they can trust us to be truthful and that we will be around when they need help or want to know more.

This librarian should join ALA and AASL so that she will have legal representation if needed.

That being said, I will be purchasing your book for my elementary library. I have a M.L.I.S. with a school library certification. It is not my job to stop a child from reading anything. ‘In Loco Parentis’ is a teacher mindset- not a librarian’s. It was not her fault or even her job to know that parent didn’t want her student reading ‘Twilight’. I had that situation happen exactly one time. I told the parent that I appreciated that she was so concerned about her student, that it was admirable, but she should have a conversation with her child about what she thinks is inappropriate and how she thinks her own student should choose books. I was prepared for her to argue (I have a “Request for Reconsideration” form as suggested by the NCTE and AASL.) I was prepared to tell her that it is not her job to control what others read. I was prepared to tell her how far I would take the fight. But, it never went that far.

I talk to my students about the ‘Student’s Right to Read’ and about Daniel Pennac’s ‘Reader’s Bill of Rights’. I also talk to them about good choices for themselves and that they should consider what their adults would say. I also tell them that if they check out a book they know they are not supposed to, I am not going to get in trouble for them and I will throw them under the bus AND I will ask their adult how long they should have recess detention. (They think I’m joking, but I’m serious.)

‘L’ is taking too much responsibility on her self which is not bad- it makes for a compassionate person and kids need that. But, it is her job as a librarian to broaden her students minds, to give them options, and to teach them to make good choices for themselves (I specifically say for themselves, because I have problems with students telling others ‘that’s a girl/boy book’. I explain that no books are just for girls or boys and that it is not their job to make that decision for someone else.). Children are resilient and they are supposed to spend this time learning their likes and dislikes. If a little checks out a book that is too ‘old’ for them, I open the book to a random page and ask them to read it out loud. Once they start stumbling, I stop them and ask if they think it’s a good choice book. Almost always they say no and put it back. If they say yes, I tell them that they can try but if it gets too tough or they don’t like it they can bring it back at any time.

A library should be a safe place where a child is free to choose, free to learn, and free from judgment.

I’m not a conventional teacher; I’m a tutor for kids of all ages. But I’m speaking right now for the student I was.

You look at a 5th grader and see a child. I see a kid a year or two away from their first kiss. I knew friends who lost their virginity at 11 or 12. The first friend to tell me they were raped was 14–and a boy, two years out of elementary school.

I knew because I was a peer. They didn’t tell their parents, or teachers. You’ll never hear about it unless it all blows up. Last year, my community was enraged to learn that a high school teacher was having an affair with his student–and she wasn’t the first he’d preyed on. Adults and parents who hadn’t had him as a teacher were shocked. Everyone else? We knew. (The state of the reporting system is another story for another day.) All kids lead secret lives, scary or benign. They need to have the resources at hand to cope.

This was not inner city. This was a small town in middle America.

When unilateral decisions are made to protect parents–and I will say right here that not putting a book in the library because kids will read it happily and willingly and parents won’t like it even though it’s age-appropriate and intended for that reading level *is* protecting parents–you are stranding the kids who need that support the most.

I was allowed to read whatever I wanted. Yes, I read stuff I wasn’t ready for. Mostly I just didn’t understand it. I had no basis to. (“‘Sleeping with?’ Well, I guess that means sleeping next to. Yeah.’) But what about the girl in my class who had a baby at 14? Maybe that book could have helped her to speak up. And she wouldn’t have found it at the public library where I did–it would have had to be at school.

Librarian, I agree that children under 13 shouldn’t be watching Avengers–a PG-13 movie designed for adults. They shouldn’t be reading Hunger Games, a series made for teenagers. But books made for readers their age, at their level, should be available even and especially when they deal with difficult topics. Because the kid who needs it the most needs it where they can have access to it: in the school library.

I appreciate both Kate and the school librarian for their conversation here, and for allowing us to be a part of it. As a mother and a writer of books for and about children and teens, I understand the librarian’s desire to protect kids. As a writer, I approach painful subjects in my books because I remember childhood pain myself, so acutely.

I’d like to start by addressing the metaphor of innocence as a “bubble,” one I’ve heard many times, and which, I think, is not a useful one. I understand what the librarian means when she says, “I want some more hours of sprinklers, mud pies, and running around with light sabers,” but these wonderful moments of fun don’t have to stop the moment kids begin to confront the complexities of our shared world. Kids are dealing with real life, already.

Most likely, your kids know something about what happened in Orlando. They are aware of planes going down. They know about walls being built between and around us. They are perceptive members of society, much earlier than many adults are comfortable admitting.

Later, the librarian writes, “So again it comes down to what I can do to get these books in the hands of the right students and not the wrong ones.” But I don’t think we can see from the outside which students are the “right” ones for a book and which students are the “wrong” ones. I would argue that any kid who picks up a book because she has a desire to read it is the “right” kid for that book, at that moment.

A book is a wonderful place to practice saying “no.” If a reader picks up a book, begins to read, and finds himself in over his head, he can close the book and walk away. Or, he can grow into the book, through the process of reading it, through his own thoughts about the material, through discussions with librarians, teachers, family, and friends.

I remember fifth grade. I was dealing with harassment from fellow students; the space shuttle falling from the sky; serious troubles at home; questions about whether or not I was headed for hell, as some of my classmates told me, since I was not baptized. I was steeped in Madonna’s music, listening to “Like a Virgin” and “Papa Don’t Preach” on my Walkman. I was flashed by a man in my very nice neighborhood. I was afraid a lot, and excited a lot, and lonely a lot. How much of this could my school librarian see? Very little, I would think. She saw a bookish girl who was anxious to please and wasn’t very good at math. She didn’t see the heart of me, because I didn’t offer it. I didn’t have the words to express it, even. I found this words in books–probably books many adults would consider to be the “wrong” books. I didn’t find them in my school library. Ours was carefully culled of material we may have needed but that could have made the parents uncomfortable.

Kids are dealing with things that even we as parents and teachers and librarians aren’t aware of. This both frightens me and makes me deeply sad. But kids are whole people, not extensions of their parents or their teachers, and we need to provide them with books that make us uncomfortable–heck, that may make THEM uncomfortable, even–because they may find words for their fears and troubles between those covers. I’ll keep writing those books. That is my job. Whether or not teachers, librarians, and booksellers provide access to my books, and books like THE SEVENTH WISH and GEORGE, books that challenge and support young people’s varied and often-unspoken needs… that is their job. Please, do it well.

I think one thing that is often missing from these conversations is the agency of the child. Kids often know quite quickly when they are not ready (or not interested) in a certain topic. Are there ways to be more proactive about informing not just the parents but the students themselves about the content of a book? Content note often get dismissed as ridiculous but I think they could be effective especially if used universally rather than just for \”controversial\” books.

Another thing that came up in this discussion is the concern that the child is unprepared to face these issues. Completely legitimate concern which, in an ideal world, would be solved by reading with adult supervision. (For example when my 11 yr old brother asked to read Hunger Games, we did it book club style: we both read it then came together to discuss.) That may not always be happening at home and I think it is an unfair burden to place on teachers and school librarians considering the expanding class sizes and shrinking resources. However could more support be built into the backmatter of these books? Could providing author\’s notes, discussion questions, and resources for more information be helpful? In many cases the kids who do \”need the book\” the most, also need the most guidance. Handing them a piece of fiction that uncovers heavy topics without having some support in place for them isn\’t good either.

I completely respect this librarian\’s point of view and it is one shared by MANY MANY teachers and librarians across North America (I\’m writing from Canada). I hope we can work together to create resources that make their jobs easier.

I am grateful that this conversation was started because I think it needs to be discussed. I disagree with one of the comments where someone wrote “it’s a teacher’s job to provide access to these books.” I have to think that the person who wrote that is clearly not a teacher because so much more goes into making these decisions than just “that is their job”. Most often in more communities than not, the job is to look at the entire student population in school community. The job is to look at how administrators and parents feel about certain subjects. The job is to look at the emotional maturity and needs of their students. The job isn’t to simply put every book on the shelf and let the kids figure it all out for themselves. That is a job for a bookseller not a school librarian. I applaud this librarian because she clearly takes her job seriously. She looks at all aspects before deciding where a book should be placed. Remember she is not saying that the book should not be available at her school just perhaps an older grade level because she clearly takes her job seriously. So that begs the question of who does the line drawing? Somebody has to draw that line for their school. Why don’t we put Eleanor and Park or 13 Reasons Why in elementary schools? Because a certain line was drawn. Somebody saw something in those books that was too mature for that age group. So why would it be unreasonable that librarians find the content of this book and some others mentioned not suitable for their particular students? What is only one side of the line in your head might not be what is on the other side of the line in someone else’s I don’t think anyone is calling students who share similarities with these characters inappropriate or wrong. I think this librarian is looking at her group, the one she is responsible for, and seems to know very well, and making a decision from there. There are many times when my daughter brought home a book from the school library that I didn’t even know she checked out. Thank goodness it was always a book that she was emotionally ready for. There were some tough topics but nothing so drastic or so specific that I felt like it would hurt her in anyway. At the same time you can be sure that if she brought home a book that was too mature for an elementary school library I would have been on the phone with that librarian right away. A book placed in the school library has to be of a certain ilk that any child could check it out and it would be OK. And when I say OK I don’t mean that the topic is sugar and candy. I mean OK that it hasn’t gone just a little too far for that age group. I just think it’s funny for people to be saying they understand why this or that book wouldn’t be in there but can’t understand the reasons behind this new book. Is there a magic line formula that I don’t know? Ms. Messner when you wrote this book were you absolutely sure in every way that it was appropriate for K through fifth grade? Because putting it out there as an upper elementary book puts it in the hands of everyone K through fifth grade. Kudos to this library for being thoughtful and respectable of her entire school community. Because THAT is her job.

I’d like to thank you both for this conversation. It feels so important that we not lose our ability, as a culture and community, to disagree thoughtfully, to create a space for real dialogue. I admire what’s happened here, and hope to see more of it.

As a mom, it’s very important to me that my kids have free access to books. I let them roam the public library, and would never tell them they couldn’t “handle” a book. This has been my policy for a long time, really since birth. As a result, we’ve had some difficult moments, when a book scared one of them, or created questions. But the end result is that my kids are very good at knowing when they aren’t ready for something, or don’t want to engage with it. They tell me, “I don’t want to hear any more about Ebola on the radio, mom, okay?” or “I don’t like books about orphans.” At a recent sleepover, my son excused himself from a video the others were watching because he knew it would give him nightmares.

I sometimes wonder if, in rushing to “save” kids from anxiety and upset, we aren’t robbing them of the lesson anxiety can teach. I wonder if the end of the process is resolution, and we’re jumping in when they’re in some middle-stage, and interuptingtheir growth. In much the same way that it messes with kids to shut off a scary movie in the middle, because they don’t get the happy ending.

All this said, I know a lot of parents who disagree with me, and I’ve gotten blowback about my own books being too scary, or having “mature” elements in them. I know my own books have been removed from shelves and schools, for these reasons. And I guess my question is how we can help schools to push back, when the staff WANT to be inclusive of all literature, but fear nervous (and potentially litigious) parents.

Because at the end of the day, I don’t believe there aren’t kids in your school dealing with drugs, or coming out, or abuse (etc. etc). Every school’s population includes kids dealing with all of these issues, and finding a book that helps kids understand themselves can be life-changing (or life saving). And not finding that book speaks volumes too. And for the other kids, who aren’t struggling in these ways– the empathy such books can help develop is equally important.

And I truly don’t believe that reading such a book will traumatize anyone. If I did, I might feel differently. But there’s a huge difference between feeling sad or angry or confused or anxious, and being traumatized.

In the end, I think we control the books kids read because WE want to belive we can give them a safe easy world to live in. Because controlling the books is so much easier than controlling their actual life experiences. Because it makes US feel better, reassured. Because it’s painful for US to see them struggle, or interact with suffering.

But every book that confused me as a kid taught me something. Every sad book made me think about emotions differently. And often those books prepared me for something I hadn’t experienced yet, but would.

I don’t think we read books that we’re “ready for.” I think books make us ready for more, they stretch us. They’re the best way to engage with new or frightening things. A baby pool, of sorts. A safe passage.

I am grateful for this discourse and distressed at the same time. So many people are writing that of course their young children know about heroin and what happened in Orlando or most kids have been exposed to drug abuse of some kind. This is a gross overestimation. Not everyone! In the school where I teach our young students are very innocent. Are there some that might be dealing with these topics? Of course it’s possible but they are few. We teach empathy and character and respecting all difference of all people. We use books and crafts and movies and many mediums. A book specifically targeting drug addiction doesn’t do a better job than a wide spread strong empathy curriculum. At this young age it’s not necessary to get into specifics. Controlling anxiety is a much greater responsibility than educating about addiction. These children whose teachers and parents want to tell them everything before they might be ready aren’t adding to their lives. They need to learn tolerance and acceptance in an age appropriate way. Rushing the process makes me sad. Let them sleep easy b

I had a lot of thoughts while reading this conversation, but many of them have already been covered by other commenters. So I\’ll just add three thoughts:

1. \”I caught students huddling in the corner and snickering at the part in the book where the boys reveals he likes other boys…. It was also a clear indicator that they are not emotionally ready for something delving deeper into the topic.\” I\’d like to suggest an alternative interpretation to that scene. They were obviously interested in the topic and also obviously in need of guidance. I\’d say huddling and snickering indicates kids who need more information, not less.

2. If a book is on a shelf, the kids who need it have access to it, and the kids who don\’t need it can avoid it. But if a book is not on a shelf at all, then only the second population is served at the expense of the first.

3. What struck me most in this librarian\’s words is something I have heard from many other teachers and librarians: Fear. There is so much fear out there: fear of angry parents getting people fired. Fear of bad publicity and media storms. Even fear of the books themselves. I just wanted to point this out because I think it would be interesting for us to look at this fear more closely: where it comes from, how it operates.

Thank you for this conversation and allowing us to see the thought and love that goes into these decisions. As a librarian, author, and parent, I, too, see many sides of this issue. In the end, I have to advocate for more access, not less for all the reasons that you (Kate) and others have stated. So, here is how I handle it in my library.

First, I am not in my libraries all the time. Currently I split my time between two schools, and I frequently go into classrooms to teach. So, a big part of the early year in the library and in the classroom is about choosing “Just Right” books. This has to do with reading level, of course, but also content. We talk about figuring out who we are as readers — what we like and what doesn’t appeal to us yet, the tone of stories that appeal to us, etc. It’s one of the skills I think a librarian needs to teach.

From there, most kids do choose Just Right books, but sometimes the choice feels a little off. L mentioned DRAMA, and I’ve had 1st graders drawn in by the bright cover who want to check it out. I ask, “Is that a Just Right book for you? Usually it’s older students who check that book out. There’s some bigger kid stuff in there.” And that typically makes them reconsider. In that case, the book was not right for the kid, but there are times when the book is at the right level, but I know some parents might wonder about the content. This year a 3rd grader wanted to check out IT’S SO AMAZING by Robie H. Harris — a perfectly normal selection for this age. But, I knew that the topic was a) one parents want to initiate on a timeline appropriate to their families and b) the sort that could disrupt the classroom for the rest of the day. So the teacher and I sent an email home and held the book at the circ desk for the student until the end of the day. No biggie.

No matter the content, if I’m not buying books because a younger student might get his or her hands on them, then I’m not serving my fourth and fifth graders. With education and management, though, I try to serve all students.

There have already been so many thoughtful responses, I’m not sure what I could possibly add other than my admiration for both of you women for willing to wade into the uncomfortable waters of disagreement in order to understand each other better. Thank you for that.

The conversation between you and this librarian highlights a common misconception that I see among many teachers, librarians, and parents. They do not understand the distinctions between terms like “middle school” and “middle grade” book categories. How can we help broaden understanding of the differences between these terms?

Thank you thank you thank you BOTH so much for sharing this conversation with the world. I’m asking the students in my children’s literature course to read it as an example of how to have a respectful conversation about selection when people have different views.