If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know that my first book for teachers, REAL REVISION: AUTHORS’ STRATEGIES TO SHARE WITH STUDENT WRITERS, was released from Stenhouse this past summer. I’ve been celebrating with a series of author interviews on the topic of real revision…the nitty gritty, make-the-book-better strategies that some of my favorite authors use when they’re revising a project.

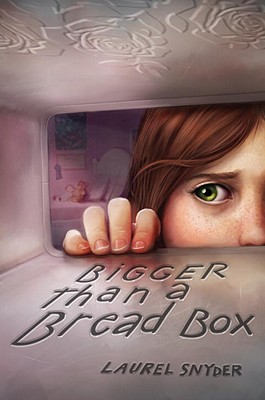

Laurel Snyder is the author of ANY WHICH WALL, PENNY DREADFUL, and her latest, BIGGER THAN A BREADBOX (my favorite Laurel Snyder book yet!). Heartbreaking, hopeful, and full of magic, BIGGER THAN A BREADBOX is the story of a girl whose life changes when the lights go out and her parents have one last argument before her mother loads the kids into the car and drives out of the state. When they land at her grandmother’s house in Georgia, Rebecca has to deal not only with her parents’ separation but also the angst of a sudden move, switching schools, and then…a magical breadbox that backfires? My heart ached for Rebecca, trying to navigate the stormy waters of a newly broken family while taking care of her little brother and dealing with questions of her own about who she wants to be at her new school. BIGGER THAN A BREADBOX is hard to explain – yes, it’s about a magic breadbox and divorce and seagulls and Bruce Springsteen and friends – but it’s one of those books that is somehow greater than the sum of its parts. Middle grade readers – especially those who have been through a parental separation – are going to read this one, love it, and hold it close for a good long time.

Laurel Snyder is the author of ANY WHICH WALL, PENNY DREADFUL, and her latest, BIGGER THAN A BREADBOX (my favorite Laurel Snyder book yet!). Heartbreaking, hopeful, and full of magic, BIGGER THAN A BREADBOX is the story of a girl whose life changes when the lights go out and her parents have one last argument before her mother loads the kids into the car and drives out of the state. When they land at her grandmother’s house in Georgia, Rebecca has to deal not only with her parents’ separation but also the angst of a sudden move, switching schools, and then…a magical breadbox that backfires? My heart ached for Rebecca, trying to navigate the stormy waters of a newly broken family while taking care of her little brother and dealing with questions of her own about who she wants to be at her new school. BIGGER THAN A BREADBOX is hard to explain – yes, it’s about a magic breadbox and divorce and seagulls and Bruce Springsteen and friends – but it’s one of those books that is somehow greater than the sum of its parts. Middle grade readers – especially those who have been through a parental separation – are going to read this one, love it, and hold it close for a good long time.

Laurel’s visiting today to talk revision, especially as it relates to this book.

Welcome, Laurel! How do you tackle the revision process? A little at a time as you write? Or all at once after you’ve finished a draft?

Both. I’m always wishing I could be one of those people who just sprints blindly through the first draft, and then goes back to read the book and start over again, with their revision hat on. But I can’t do that. I’m a tweaker. From the very beginning, I fiddle with each line. I think this is because underneath it all I’m still really just a poet-pretending-to-write-novels. My favorite part of writing isn’t plotting or world-building, it’s sculpting phrases, sentences, lines. When I don’t allow myself that pleasure, it’s not as much fun to write.

That said, as I get further into the book, and the plot takes over, I tend to move faster and get sloppier. So my first drafts are always imbalanced. The first half of each feels pretty clean, and the second half of each has GLARING issues, big sections of mess that need to be fixed. The first chapter of the first draft can take me a month to write. The last chapter can take me a day.

But then comes the joy of a second draft. Of tinkering.

Do you have a favorite revision strategy that helps with any particular part of the process?

I have no idea if other people do this, but I keep a BIG list. As I proceed into my first draft, I keep a list of “issues.” It’s a separate document, because if I had to see it each time I worked, I’d never move forward. On it you’ll find notes to myself about certain moments, sections of dialogue I need to work in, reminders to myself about themes that need to be developed through the book, or research I need to do for a specific scene, as well as logic problems and chunks od text I’ve edited out already. This list just grows and grows, and then, when I finally have a draft, I’ve got about ten pages of editorial notes to myself. Then I print the list out, and chop it up into scraps of paper, so that as I read the draft, I can paperclip them into the places they need to be handled.

Like, on my list for the book I’m writing right now, I have a note that says, “The girls need to use a photoboth at some point? Woolworths?” This is because later in the book, a picture needs to surface, as a plot point. But I only figured that out late in the game. So rather than stop in the middle of the book, go back, write in a photobooth, I make a note. Then, when I’m done with the draft, I’ll snip that from the list, and then as I’m reading on my first pass, I’ll be hunting for a place to stick it into the draft.

It’s very concrete, this process. Like a puzzle. Totally removed from the actual “writing” of the book, and that’s satisfying to me.

How do you revise to make sure your pacing works for the story you’re telling? Were there any parts of your original manuscript for this book that ended up being cut?

Oh, gosh. Pacing is my weak spot, because I like to read slow books myself, and I tend to write slow books, so I really rely on outside readers to help me with this. But yes, because of that, VAST sections and key characters often get cut.

The big thing that was slashed from Bigger than a Bread Box to assist with pacing was a character, a guy named Japheth. In the original draft, Rebecca moved to Atlanta, and made friends with her next-door neighbor, a Caymanian kid named Japheth. His father still lived far away, in the islands, and his family had real financial issues. He was going to be a chance for Rebecca to see that as hard as her life was, she had a lot to be grateful for. He was also just a really sweet character, and kind of mild love interest, in a non-sexy way. It killed me to cut him from the book, but in the end I felt like Rebecca’s loneliness was its own character, and taking Japheth out moved the story along much faster.

I still miss him.

(Maybe he can make an appearance in another book?) Anyway, let’s talk characters. What strategies do you use when you’re revising to make them feel real & believable?

Oh, that’s so hard, because in each book my process of writing characters has changed. With Rebecca, it’s easier, in some ways, because she’s basically ME. So I just have to feel for the moments when *I* wouldn’t do something, or *I* wouldn’t react a certain way. But that’s not usually how it works.

Often for me, the first step to character revision is about making sure that in trying to make a character consistent, I haven’t made them into a stereotype of themselves. I think a lot of books today make characters BIG by giving them “noticeable characteristics.” Like, a girl who always tosses her hair, or a boy who cries at everything, or a woman who says “Zoinks!” This works in sitcoms, I guess, but I’ve never read a truly incredible book where this worked, unless it was a satire or a parody or something.

So one thing I do is “search” my manuscript to see how often certain words or phrases get used. Like, Emma, in Any Which Wall, was perpetually, “staring at someone, not knowing quite what to say,” and she did a lot of “blinking” or “looking like she wanted to ask a question.” You can get away with doing something a few times, but that’s not actually building a character. The character comes from inside. If you strip about the gimmicks, and the character doesn’t stand up to the process, you don’t have a character, you have a paper doll. You can always layer these moments back in, but an important part of revision for me is making sure I’m not relying on them. Make sense?

Absolutely! I think sometimes when we see the shiny finished book, it’s easy to forget how challenging the work of revision can be. What was the biggest revision job for this particular book? (timeline changes, new chapters, rearranging scenes, etc?)

Well, I already told you about the thing with Japheth. I guess the other really big thing has to do with the climax of the book. I don’t want to spoil the ending of the story, but I had a hard time figuring out how BIG to make the drama of that scene. This is less about plot, I think, and more about tone, which is sometimes a hard thing to discuss, because it’s so slippery.

But basically, the climax of Bigger than a Bread Box is a sort of “adventure book climax” and the book, though magical, is really a “coming of age” book. Initially, Rebecca ran away from home for this scene, crossed state lines, etc. But it was just TOO MUCH. I found myself afraid that the drama of all that would overshadow the real climax of the book, which needed to be inside the characters. I almost went even further. I almost chopped that scene WAY back. But I felt like the book needed a big moment, a wake-up moment. And in real life, kids DO have intense dramatic things happen, so I ended up with a compromise. But I struggled with that scene a lot.

Did this book keep its original title, or did it change along the way?

Original title. I’ve actually never changed a title, ever. Isn’t that funny? I almost always know the title before I know the plot. The book I’m writing now, Seven Stories Up (a prequel to Bigger than a Bread Box) feels like it might change. I keep waffling on it.

(If you weren’t such a lovely person, Laurel, I’d hate you for this. I think EVERY one of my titles has changed!) So where did the title BIGGER THAN A BREADBOX come from?

The idea for the book came from a car ride. My husband and I were driving to Iowa, with the kids in the car, and I said to him, “What if, in a book, a kid had a box that gave them whatever they wanted, but then they found out where the things were COMING FROM?” Because we were trapped in the car for the next 20 hours, I had nothing to do but think about that. I kept whipping out my laptop, typing on my knees, making notes, as we drove along. By the time we got to Iowa, it had become a bread box. And the title just seemed completely obvious after that.

I’m a big believer that boredom and silence are required for generating ideas. There’s not enough silence in the world today. Silence is KEY to revision too.

Anything else you’d like to say about revising this book?

Hmmm. I do have something else, which is that I wrote THIS book about real memories. My parents divorced when I was eight years old, and my mom moved me from my childhood home in the seventh grade. I’d be lying if I pretended this book wasn’t basically about my emotions during those two chapters of my life. But part of revision, when you’re writing from memories, is about getting out of your own way. Rebecca is a shadow of me, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t have to respect the character and the book enough to set my own emotions aside when revising. That turned out to be hard for me. I’d never had that experience before. When I got to the end of the book, and realized that the end was different than I’d planned–that was hard, and weird. In the end, the single greatest rule of revision is that you have to LISTEN to the book, get out of the way of your own intent, write the book that wants to be written. When you’re navigating your own emotions, that’s even harder. I was shocked at how amateur I felt. I wanted to make Annie and jim (Rebecca’s parents) love each other. But that wasn’t for the book, that was for me.

Thanks for joining us Laurel!

And everybody else…you need to read this book if you haven’t already. Ask your library for it, or get it from your local indie bookseller.

“I’m a big believer that boredom and silence are required for generating ideas.” — What an important concept. My boss a million years ago said this to me and he was right! It’s not easy to sit in silence sometimes, but so much good comes from it.

Inspiring interview! Thanks Laurel and Kate!

Donna

hi mrs.messner my friends and i are doing a research on you and i was wondering if u could answer these questions for me i go to Sparta Middle School and here’s my questions

when is your birthday?

Day of Week?

Parent Occupation?

lifestyle?

plz answer them thank you mickey!!!!

Hi, Mickey! Here are my responses to your questions:

when is your birthday? the day before Independence Day!

Day of Week? I don’t really understand this question. It’s Wednesday today…

Parent Occupation? My parents were both educators.

lifestyle? I don’t really understand what you’re asking here either – you’d need to elaborate for me to be able to answer.

Good luck with your project!

~Kate