Hi there! And welcome to the World Read Aloud Day author Skype volunteer list for 2020!

If you’re new to this blog, I’m Kate Messner, author of more than thirty books for kids, former middle school teacher, and forever reader. Reading aloud is one of my favorite things in the world. When I was a kid, I was the one forever waving my hand to volunteer to read in class, and still, I’ll pretty much read aloud to anyone who will listen.

For the past few years, I’ve helped out with

LitWorld’s World Read Aloud Day by pulling together a list of author volunteers who would like to spend part of the day Skyping with classrooms around the world to share the joy of reading aloud.

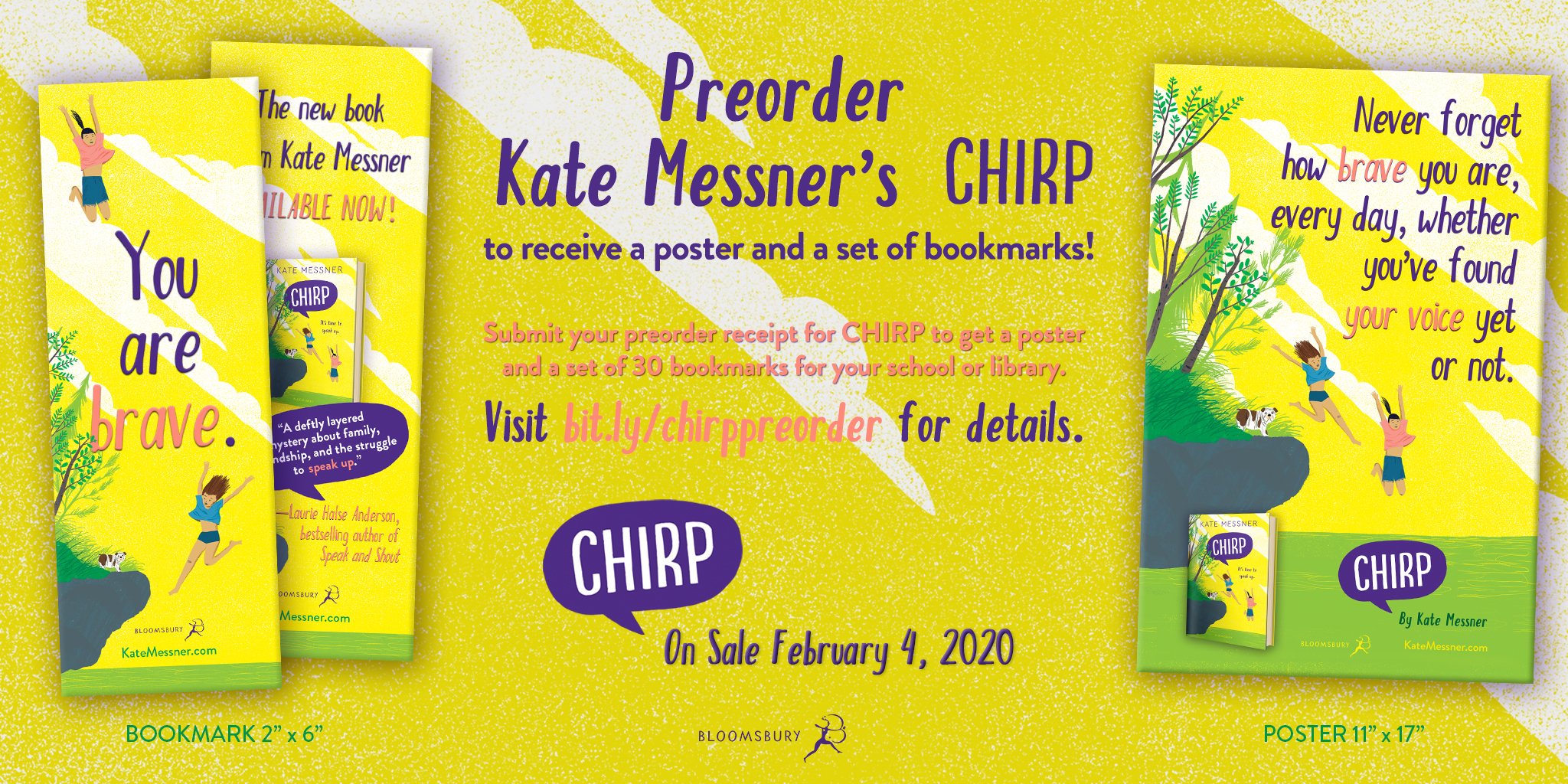

This WRAD, I won’t be available to Skype into classrooms myself, but it’s for a great reason – I’ll be on book tour for my new novel! CHIRP is a mystery set on a cricket farm and a coming-of-age story that’s earned three starred reviews. You can read more about it here.

And I have a favor to ask… If you’ve used my World Read Aloud Day Skype lists over the years and appreciate this resource, would you consider pre-ordering a signed copy? You can do that here, through my local indie, The Bookstore Plus. Just make a note in the comments about how you’d like it signed. You can also order an unsigned copy from any bookseller you like. To say thanks, Bloomsbury will send you a CHIRP poster and a class set of signed bookmarks! Details on that are here.

Also…if you’d like to pre-order a copy as a holiday gift, I’ll happily mail you a personalized, signed letter and bookmark that you can wrap or tuck in a stocking to let your reader know a new signed book will be on the way. Here’s how to request that.

Okay…on to this year’s list!

WORLD READ ALOUD DAY IS FEBRUARY 5, 2020

The authors listed below have volunteered their time to read aloud to classrooms and libraries all over the world. These aren’t long, fancy presentations; a typical one might go like this:

- 1-2 minutes: Author introduces himself or herself and talks a little about his or her books.

- 3-5 minutes: Author reads aloud a short picture book, or a short excerpt from a chapter book/novel

- 5-10 minutes: Author answers a few questions from students about reading/writing

- 1-2 minutes: Author book-talks a couple books he or she loves (but didn’t write!) as recommendations for the kids

If you’re a traditionally published author or illustrator who would like to be added to the list next time I update, please fill out this form.

If you’re a teacher or librarian and you’d like to have an author Skype with your classroom or library on World Read Aloud Day, here’s how to do it:

- Check out the list of volunteering authors below and visit their websites to see which ones might be a good fit for your students.

- Contact the author directly by using the email provided or clicking on the link to his or her website and finding the contact form. Please be sure to provide the following information in your request:

- Your name and what grade(s) you work with

- Your city and time zone (this is important for scheduling!)

- Possible times to Skype on February 5th. Please note authors’ availability and time zones. Adjust accordingly if yours is different!

- Your Skype username

- A phone number where you can be reached on that day in case of technical issues

- Please understand that authors are people, too, and have schedules and personal lives, just like you, so not all authors will be available at all times. It may take a few tries before you find someone whose books and schedule fit with yours. If I learn that someone’s schedule for the day is full, I’ll put a line through their name – that means the author’s schedule is full, and no more visits are available. (Authors, please send an email to me know when you’re all booked up! And please note that due to travel and other obligations, it may take up to a week for me to update.)

World Read Aloud Day – Skyping Author Volunteers for February 5, 2020

Authors are listed here, along with publishers, available times, and the age groups for which their visits are best suited. Please note that while they’re divided by age groups, some folks on the Elementary list might also be great for your Middle School Readers, so feel free to explore the whole list.

FOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL READERS

Susan B. Katz

Scholastic, Random House, Barefoot, Bala, Callisto

Elementary

PST prefer midday (Also, I am Spanish bilingual)

www.susankatzbooks.com

Susankatz25@gmail.com

kevin sylvester

Simon and Schuster/Groundwood

Elementary

Eastern 8am-8pm

kevinsylvesterbooks.com

sylvesterartwork@gmail.com

Jody Feldman

HarperCollins/Greenwillow

Elementary

8:30 am – 4:00 pm CST

http://jodyfeldman.com

jody@jodyfeldman.com

Loree Griffin Burns

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Henry Holt, Millbrook, Charlesbridge

Elementary

Eastern US, 9am-5pm

www.loreeburns.com

lgb@loreeburns.com

Liz Garton Scanlon

Beach Lane Simon & Schuster

Elementary

Central time zone, 9:30 am-2:30 pm

liz@lizgartonscanlon.com

liz@lizgartonscanlon.com

Megan Blakemore

Bloomsbury and Aladdin/Simon& Schuster

Elementary

8:30-11:30 EST

www.meganfrazerblakemore.com

megan.frazer@gmail.com

KIM TOMSIC

HarperCollins and Chronicle

Elementary

Pacific Time 9 AM-4PM

www.KimTomsic.com

ktomsic@gmail.com

Jess Redman

Macmillan

Elementary

9:30 to 12 EST

www.jessredman.com

jessicaeredman@gmail.com

Kim Baker

Random House

Elementary

PST; 9 a.m-2p.m.

https://www.kimbakerbooks.com

kim@kimbakerbooks.com

Anne Marie Pace

Disney-Hyperion, Abrams, Beach Lane/S&S

Elementary

9 – 12 Eastern

http://www.annemariepace.com

annemarie@annemariepace.com

Fleur (F.T.) Bradley

HarperCollins Children’s

Elementary

Mountain time, flexible

www.ftbradley.com

Fleur@ftbradley.com

Juana Martínez-Neal

Candlewick and Roaring Brook Press

Elementary

PHX – 9am-12pm and 1pm-3pm

juanamartinezneal.com

me@juanamartinezneal.com

Tracey West

Scholastic

Elementary

EST, 9 am – 5 pm

www.traceywest.com; @traceywestbooks on Twitter;

purewest@verizon.net

Sarah Aronson

Beach Lane Books (Simon and Schuster)

Elementary

Central 8am-5pm

http://www.saraharonson.com

sarah.n.aronson@gmail.com

Laura Gehl

Albert Whitman

Elementary

EST 10-2

www.lauragehl.com

laurameressa@gmail.com

Miranda Paul

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Penguin Random House, Lerner, Holiday House

Elementary

9 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Central Time Zone (US)

www.mirandapaul.com

mirandapaulbooks@gmail.com

Abby Cooper

Macmillan, Charlesbridge

Elementary

CST. Available 8 AM – 12 PM

Www.AbbyCooperAuthor.com

AbbyRCooper@gmail.com

Carmella Van Vleet

Holiday House, Charlesbridge, Nomad Press

Elementary

9:00 to 3:00 EST

www.CarmellaVanVleet.com

carmellavanvleet@yahoo.com

Erica S. Perl

Penguin Random House

Elementary

9 am – 11 am EST

ericaperl.com

erica@ericaperl.com

Janet Sumner Johnson

Capstone

Elementary

9:00 AM – 3:00 PM MST

http://janetsumnerjohnson.com/

pbjsociety@gmail.com

Michelle Cusolito

Charlesbridge

Elementary

EASTERN 1-3 pm

http://www.michellecusolito.com/

michelle@michellecusolito.com

Annie Silvestro

Doubleday, HarperCollins, Sterling

Elementary

9am -2:30pm EST

www.anniesilvestro.com

anniesilvestro@gmail.com

Sue Fliess

Albert Whitman, Sky Pony, Running Press

Elementary

EST, 9am-2pm

Www.suefliess.com

sue.fliess@gmail.com

Robin Yardi

Lerner

Elementary

PST 6am-2pm

www.RobinYardi.com

robinyardi@mac.com

Susan Tan

Roaring Brook: Macmillan

Elementary

EST, and pretty much all day! (Let’s say 9-6, but I can be flexible).

www.susantanbooks.com

Susanshaumingtan@gmail.com

Mae Respicio

Wendy Lamb Books/Random House

Elementary

PST – fyi I marked “elementary” (3/4/5) but could also do middle school! Was not able to mark both… thank you for this opportunity and for organizing! 🙂

www.maerespicio.com

mae@maerespicio.com

Hayley Barrett

Candlewick Press, Beach Lane Books, Holiday House, Barefoot Books

Elementary

9-12 EST

hayleybarrett.com

hayleybarrettwrites@gmail.com

Jessica Rinker

Bloomsbury

Elementary

EST–anytime

www.jessicarinker.com

jessrinker3@gmail.com

Laura Shovan

Random House and Clarion Books

Elementary

EST 9-5

https://laurashovan.com

laurashovan@gmail.com

Jenn Bailey

Chronicle

Elementary

Central Time Zone 9:00 a.m. – 3:30 p.m.

www.jennbailey.com

jenn.c.bailey@gmail.com

Amanda Rawson Hill

Boyds Mills and Kane, Magination Press, Charlesbridge

Elementary

PST available 8-12

Amandarawsonhill.com

Amanda.rawaon.hill@gmail.com

Supriya Kelkar

Sterling

Elementary

EST 9:10 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.

www.www.supriyakelkar.com

supriyakelkarbooks@gmail.com

Dee Romito

Aladdin/S&S, Little Bee Books

Elementary

Eastern

9-2

deeromito.com

dee@deeromito.com

Elaine Vickers

HarperCollins

Elementary

Mountain, 8-12:30 and 2:30-5

elainevickers.com

elainebvickers@hotmail.com

Stephanie Campisi

Familius, Sourcebooks

Elementary

9am-12pm PT

www.stephaniecampisi.com

stephanie.campisi@gmail.com

Chana Stiefel

Houghton Mifflin Harco

Elementary

9-11 am EST

https://chanastiefel.com/

stiefelchana@gmail.com

Lisa Schmid

Northstar Editions/ Jolly Fish Press

Elementary

Pacific Standard Time/ 10:00-1:00

www.lisalschmid.com

lisa.schmid@sbcglobal.net

Sheetal Sheth

Bharat Babies

Elementary

9:30am-1pm EST

www.sheetalsheth.com

sheetal@sheetalsheth.com

Lisa Rogers

Schwartz & Wade

Elementary

EST /between 12-12:30 or after 3 p EST

lisarogerswrites.com

lisarogerswrites@gmail.com

Saadia Faruqi

Capstone

Elementary

9 am to 2 pm Central time

www.saadiafaruqi.com

saadia@saadiafaruqi.com

Marcy Campbell

Penguin

Elementary

9:30 to 3:00 EST

Www.marcycampbell.com

marcycampbellbooks@gmail.com

Nancy Churnin

Albert Whitman & Company; Creston Books/Lerner Books

Elementary

CST, daytime

https://www.nancychurnin.com

nancychurnin@mac.com

Lindsay Leslie

Page Street Kids

Elementary

CST, available from 8:30 a.m.-2 p.m.

https://lindsayleslie.com/

lindsaylleslie@hotmail.com

Tami Lewis Brown

Disney/Hyperion, Philomel and FSG

Elementary

Eastern Time Zone Hours flexible

www.TamiLewisBrown.com and www.BrownandDunn.com

tamilewisbrown@gmail.com

Jill Diamond

Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Elementary

10:00 AM – 3:30 PM PST

www.jilldiamondbooks.com

jilldiamond78@gmail.com

Joy Keller

Henry Holt/The Innovation Press

Elementary

EST–10:00 am -2:00 pm

joykellerauthor.com

joykellerauthor@gmail.com

Tim McCanna

Scholastic, Simon & Schuster, Abrams

Elementary

Pacific (California) 9:30am – noon

www.timmccanna.com

tsmccanna@gmail.com

Larissa Theule

Abrams, Bloomsbury

Elementary

Pacific, mornings

larissatheule.com

ltheule@gmail.com

Holly M. McGhee

Macmillan

Elementary

Eastern 10 – 3

hollymcghee.com

hmcgheewriter@gmail.com

Lowey Bundy Sichol

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Elementary

CT, available 9am-3pm

www.LoweyBundySichol.com

Lowey@LoweyBundySichol.com

Jane Kohuth

Penguin Random House, Kar-Ben

Elementary

10:00 AM – 3:00 PM EST

Http://www.janekohuth.com

Jane@janekohuth.com

Sarah Jane Marsh

Disney-Hyperion

Elementary

8:00 AM – 2PM PST

sarahjanemarsh.com

sarah@sarahjanemarsh.com

Emma Wunsch

Abrams

Elementary

8am-3pm EST

Mirandaandmaude.com

emmalucy@gmail.com

Lisa Kahn Schnell

Charlesbridge

Elementary

EST, 7:30am until 6pm

lisakschnell.com

lisakschnell@yahoo.com

Laurie Wallmark

Sterling Children’s Books

Elementary

ET, all day

www.lauriewallmark.com

laurie@lauriewallmark.com

Sarah Grace Tuttle

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, Creative Editions, Aladdin

Elementary

Eastern, 10 AM – 2 PM

www.sarahgracetuttle.com

tuttlesarahg@gmail.com

Buffy Silverman

Millbrook Press/Lerner

Elementary

Eastern; 10:00 am–2:00 pm

www.buffysilverman.com

buffy@buffysilverman.com

Laura Murray

GP Putnam’s Sons

Elementary

EST, 8:30 – 3:00

www.LauraMurrayBooks.com

LauraMurrayBooks@gmail.com

Nidhi Chanani

Macmillan

Elementary

Pacific, between 10am-3:30pm

Everydayloveart.com

Nidhinecco@gmail.com

Raakhee Mirchandani

Bharat Babies

Elementary

EST; flexible

Super Satya Saves the Day https://www.amazon.com/dp/1643071173/ref=cm_sw_r_cp_api_i_AU8PDb8DXREYN

raakhee.mirchandani@gmail.com

Leslie Bulion

Peachtree Publishers, Charlesbridge

Elementary

Eastern Time Zone – available 7am-5pm

www.LeslieBulion.com

lesliebulion@gmail.com

Jake Burt

Feiwel and Friends/Macmillan

Elementary

Eastern; 1:00-2:00 PM

www.jburtbooks.com

jake@jburtbooks.com

ROBIN NEWMAN

Creston Books; Sky Pony Press

Elementary

EST; 10 am – 1 pm

www.robinnewmanbooks.com

rnewman504@nyc.rr.com

Mariana Llanos

Penny Candy Books

Elementary

Central 10am

www.marianallanos.com

mariana_llanos@hotmail.com

Ishta Mercurio

ABRAMS Books for Young Readers

Elementary

Eastern time; available 9am-5pm

www.ishtamercurio.com

ishtamercurio@icloud.com

Lija Fisher

Farrar Straus & Giroux (BYR)

Elementary

Mountain time, I’m available anytime!

LijaFisher.com

misslija@hotmail.com

Shawna J. C. Tenney

Sky Pony Press

Elementary

MDT, all school hours

www.shawnajctenney.com

shawna@shawnajctenney.com

Erin Soderberg Downing

Random House Children’s Books

Elementary

CST/9:30-3

Www.erinsoderberg.com

Erin@erinsoderberg.com

Karen Romano Young

Chronicle

Elementary

EST, 10-4

Karenromanoyoung.com

Wrenyoung@gmail.com

Dana Middleton

Chronicle

Elementary

Time zone PST; Available 8am -1:30pm PST

Danamiddletonbooks.com

Dana@danamiddletonbooks.com

Annette Bay Pimentel

Nancy Paulsen, Charlesbridge

Elementary

Pacific, 7 am-3pm

Annettebaypimentel.com

annettepimentel@gmail.com

Shauna Holyoak

Disney-Hyperion

Elementary

MST 10am – 2pm

www.shaunaholyoak.com

s.holyoak@yahoo.com

Sarah Sullivan

Candlewick

Elementary

EST 8:00 a.m. – 5:30 p.m.

www.sarahsullivanbooks.com

sarahsull026@cox.net

Debbi Michiko Florence

Macmillan, Scholastic, Capstone

Elementary

EST, between noon and 3 PM

http://debbimichikoflorence.com/

author@debbimichikoflorence.com

Anna Raff

Candlewick

Elementary

EST, 9 AM to 4 PM

http://www.annaraff.com

anna@annaraff.com

Artemis Roehrig

Scholastic

Elementary

EST 9-noon

www.artemisroehrig.com

ArtemisRoehrigWriter@gmail.com

Melissa Stoller

Clear Fork Publishing

Elementary

Eastern (New York) 10-2

www.MelissaStoller.com

Mlstoller@aol.com

Betsy Devany

Henry Holt/Christy Ottaviano Books

Elementary

Anytime between 9 EST and 5 EST

www.betsydevany.com

betsydevany@comcast.net

Debbie Ridpath Ohi

Simon & Schuster Children’s

Elementary

(EST) 10-11:15 am EST

http://DebbieOhi.com

Corey Ann Haydu

Katherine Tegen/Harper Collins, Simon Pulse/S&S

Elementary

10am-5pm EST

www.coreyannhaydu.com

coreyann@gmail.com

Shawn K. Stout

Philomel

Elementary

ET; 9am to 3:30

www.shawnkstout.com

shawn@shawnkstout.com

Victoria Piontek

Scholastic

Elementary

PST 9-2

https://www.victoriapiontek.com/

victoriapiontekbooks@gmail.com

Daphne Kalmar

Macmillan

Elementary

EST 9-12

www.daphnekalmar.com

daphnekalmar@gmail.com

Laura Renauld

Atheneum

Elementary

Eastern; 9:00-2:00

www.laurarenauld.com

laura@laurarenauld.com

Heather L. Montgomery

Bloomsbury, Charlesbridge, Millbrook, Capstone

Elementary

Central Time, After 1 PM (have a school visit in the AM)

www.HeatherLMontgomery.com

sipsey21@hotmail.com

Erin Dealey

Sleeping Bear, Atheneum / Caitlyn Dlouhy Books/ S&S, Harper Collins, Kane Miller

Elementary

Pacific–very flexible

www.erindealey.com

erin@erindealey.com

Margie Markarian

Sleeping Bear Press

Elementary

Eastern Standard; 9:00-12:00

www.margiemarkarian.com

margiemarkarian27@gmail.com

Claire Lordon

Little bee, sterling, Albert Whitman

Elementary

Pacific 9-12am

www.clairelordon.com

claire.lordon@gmail.com

Erin Teagan

Clarion and Scholastic

Elementary

EST, available 8am-4pm

www.erinteagan.com

teaganek@hotmail.com

Dusti Bowling

Sterling Children’s Books, Little, Brown

Elementary

11:00-4:15 EST

https://www.signupgenius.com/go/10c0944aea828a3fc1-skype

dustibowlingbooks@gmail.com

Jennifer Hansen Rolli

Penguin Random House

Elementary

EST 9-3

https://www.jenniferhansenrolli.com/b-o-o-k-s

jhansenrolli@gmail.com

Any Fauzianie

Scholastic, Random House

Elementary

1 PM

www.beaconacademy.net

any.fauzianie@beaconacademy.net

E.D. Baker

Bloomsbury

Elementary

10-4pm EST

www.talesofedbaker.com

edbakerbooks@gmail.com

Susan Richmond

Peachtree Publishing Company

Elementary

EST 2 to 5 pm

www.susanedwardsrichmond.com

susanrichmond@verizon.net

Monica Carnesi

Nancy Paulsen Books

Elementary

EST 9:00 am to 4:00 pm

www.monicacarnesi.com

monicacarnesi@mac.com

Amanda Shepherd

Chronicle / Harper collins

Elementary

Pacific coast 930 am – 11:00

AmandaShepherdillustration.com

Shepherdamanda@yahoo.com

Christine Evans

Innovation Press

Elementary

9am-12pm PST

http://pinwheelsandstories.com

christinenancyevans@gmail.com

Jenna Grodzicki

Lerner/Millbrook Press

Elementary

EST 9:30am-3:00pm

www.jennagrodzicki.com

jennagrodz@live.com

Kirsten Larson

Calkins Creek

Elementary

Pacific Standard 8-9:15 am, 11:45 am-1:30 pm

Www.kirsten-w-Larson.com

Creatingcuriouskids@gmail.com

Elaine Kiely Kearns

Albert Whitman

Elementary

EST b/w 9:30am-12:30pm

www.kidlit411.com

ekearns44@gmail.com

Carole Estby Dagg

Penguin

Elementary

Pacific/west coast time zone 8 – 3 my time

www.CaroleEstbyDagg.com

carole_dagg@yahoo.com

Cynthia Reeg

Jolly Fish Press/North Star Editions

Elementary

CST 10:00-12:30

www.cynthiareeg.com

Cynthiareegauthor@gmail.com

Darby Karchut

Owl Hollow Press

Elementary

MST; any time is fine with me

www.darbykarchut.com

darbykarchut@gmail.com

Mara Rockliff

Penguin/Putnam

Elementary

10 am – 4 pm EST

mararockliff.com

mararockliff@gmail.com

Aimee Reid

Random House; Abrams Books

Elementary

EST 10-12 and 2-3

www.aimeereidbooks.com

A.reid@bell.net

Anjali Amit

Hemkunt

Elementary

PST prefer 9am to 11am

www.bookreviewsgalore.com and thefabletable.com

anjali.amit@gmail.com

Sara Levine

Millbrook/Lerner

Elementary

EST, 9AM to 7 PM

www.saralevinebooks.com

saraclevine@aol.com

Dawn Prochovnic

West Margin Press and ABDO

Elementary

Pacific 9am-1pm

https://www.dawnprochovnic.com/

dawnp@smalltalklearning.com

Patricia Newman

Millbrook Press/Lerner

Elementary

Pacific – 7:00 am – noon Pacific

https://www.patriciamnewman.com/

newmanbooks@live.com

Carrie Pearson

Charlesbridge

Elementary

EST all day

Www.carriepearsonbooks.com

Carrieapear@aol.com

David A. Kelly

Random House Books for Young Readers

Elementary

Mountain 9am – 6pm

www.davidakellybooks.com

davidakelly@gmail.com

Amy Ludwig VanDerwater

Scholastic, Clarion, Boyds Mills & Kane

Elementary

8:15am – 10:15am EST

www.amyludwigvanderwater.com

amy@amylv.com

Christina Soontornvat

Scholastic

Elementary

Central 9am-1pm

www.soontornvat.com

csoontornvat@gmail.com

Mia Wenjen

Lee and Low Books

Elementary

EST 8am to 2pm

https://www.pragmaticmom.com/

pragmaticmomblog@gmail.com

Margaret Chiu Greanias

Running Press Kids

Elementary

PST, 9:30-11:30, 1-2

margaretgreanias.com

margaret.c.greanias@gmail.com

Mark hoffmann

Knopf (Randomhouse)

Elementary

EST. 9am-2pm

www.studiohoffmann.com

Mh@studiohoffmann.com

Marianne Malone

Penguin/Random House

Elementary

I’m in eastern but available for all zones during school hours

mariannemalone.com

mariannemalonebooks@gmail.com

Megan Dowd Lambert

Charlesbridge

Elementary

EST any weekday 9-1

www.megandowdlambert.com

Megan@megandowdlambert.com

Stephanie Lucianovic

Sterling Children’s

Elementary

Pacific 9-1:30 M-F

stephanielucianovic.com

SVWL22@gmail.com

Diane Magras

Kathy Dawson Books/Penguin Young Readers

Elementary

EST: 8:00 – 8:20 AM, 8:30 – 8:50 AM, 9:00 – 9:20 AM, 9:30 – 9:50 AM

https://www.dianemagras.com

diane@dianemagras.com

Shauna LaVoy Reynolds

Dial / Penguin

Elementary

Central time, 8-11 central.

shaunalavoyreynolds.com

shaunalreynolds@gmail.com

Sarah Scheerger

Penguin Random House, Kar-Ben, Two Lions, Blue Apple, Albert Whitman, Carolrhoda

Elementary

I’m in California, but I’d like to skype with the east coast before work. It would be best for me to skype at 6am- 7am (Pacific Standard time) which would be 9-10am (EST)

www.sarahlynnbooks.com

sscheerger@yahoo.com

Laura Dershewitz & Susan Romberg

The Innovation Press

Elementary

8am-8pm Central

@LDersh_SRom (Twitter)

lauradershewitz@gmail.com; sromberg.work@gmail.com

Anica Mrose Rissi

Disney-Hyperion / S&S / HarperCollins

Elementary

Eastern time zone; available from 10am onward

anicarissi.com

anicamroserissi@gmail.com

Ariel Bernstein

Simon & Schuster

Elementary

EST, 8:30am-10:00am

Arielbernsteinbooks.com

A3bernstein@gmail.com

Kelly Carey

Charlesbridge

Elementary

EST – 9am – 4pm

www.kcareywrites.com

kellycarey508@gmail.com

Kate Berube

Abrams

Elementary

Pacific – 9am to 1pm

www.kateberube.com

kate.a.berube@gmail.com

Lindsay H. Metcalf

Albert Whitman, Calkins Creek, Charlesbridge

Elementary

CST – 8:30 am-3 pm CST

lindsayhmetcalf.com

lindsay@lindsayhmetcalf.com

Julie Segal Walters

Simon and Schuster

Elementary

10:30 a.m. – 2:30 p.m. Eastern time

www.juliesegalwalters.com

julie.segal.walters@gmail.com

Laura James

Bloomsbury

Elementary

GMT

www.laurajamesauthor.com

laurajames_@me.com

Rebecca Flansburg

Audrey Press

Elementary

Central (Between 10 a.m. and 2:00 p.m.)

https://audreypress.com/portfolio/sissy-goes-tiny-by-rebecca-flansburg-and-ba-norrgard/

rebeccaflansburg@gmail.com

Valarie Budayr

Audrey Press

Elementary

Eastern 9-3

www.audreypress.com or www.valariebudayr.com

budayr@gmail.com

Sandy Stark-McGinnis

Bloomsbury

Elementary

Pacific Time: 12:05-12:40

sandystarkmcginnis.com

starksandy@hotmail.com

Ella Schwartz

Bloomsbury, National Geographic Kids

Elementary

9am-3pm (Eastern)

www.ellasbooks.com

ella@ellasbooks.com

Megan Maynor

HarperCollins, Knopf

Elementary

CST 10am-3pm

meganmaynor.com

mmaynor@jamaynor.com

Tracy Subisak

Roaring Brook, Sasquatch, Boyds Mills

Elementary

9:30 am – 11:30am, 2pm – 4 pm PST

tracysubisak.com

tracysubisak@gmail.com

Jessica Burkhart

Simon & Schuster

Elementary

Central time and available any time

www.jessicaburkhart.com

jessica.ashley87@gmail.com

Hallee Adelman

Albert Whitman

Elementary

EST 10-2

Halleeadelman.com

Hallee@adelmans.net

Suzanne Morris

Charlesbridge

Elementary

Eastern 10:00AM – 2:00PM

www.suzannemorrisart.com

suzannemorrisart@gmail.com

Lauren Magaziner

HarperCollins

Elementary

EST (9 am to 5 pm)

laurenmagaziner.com

laurenmagazinerbooks@gmail.com

Karina Yan Glaser

HMH Books for Young Readers

Elementary

9am – 2pm Eastern Time

www.karinaglaser.com

karina.yan.glaser@gmail.com

Meredith Davis

Scholastic Focus

Elementary

Central Time Zone, available after 1PM Central time

https://meredithldavis.com/

meredithd@me.com

Andria Warmflash Rosenbaum

Apples & Honey Press, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Scholastic Press, Sleeping Bear Press

Elementary

EST, 9:00am -12:00 am

www.andriawarmflashrosenbaum.com

andria.rosenbaum@gmail.com

Constance Lombardo

HarperCollins

Elementary

EST 11 – 3:00

www.constancelombardo.com

conlombardo@hotmail.com

Monica Tesler

Simon & Schuster

Elementary

8-2 EST

monicatesler.com

monicatesler@gmail.com

Wendy McLeod MacKnight

Greenwillow Books

Elementary

AST – all day

Wendymcleodmacknight.com

Wendymcleodmacknight@gmail.com

Jo Watson Hackl

Random House Children’s Books

Elementary

Eastern standard time, 10-1 pm

Www.johackl.com

Jo@johackl.com

Lori Richmond

Scholastic, S&S, Harper Collins

Elementary

EST 10 am – 2 pm

LoriDraws.com

lori@loridraws.com

Karen Romano Young

Chronicle

Elementary

EST 9 – 3

karenromanoyoung.com

wrenyoung@gmail.com

Jane Kelley

Feiwel and Friends, Random House Children’s Books, Grosset and Dunlap

Elementary

Central Time Zone. I’m available from 9CST until 4CST

http://janekelleybooks.com

Laura Sassi

Zonderkidz (Part of HarperCollins) and Sterling Children’s Books

Elementary

Eastern Time Zone 9 – 2

www.laurasassitales.wordpress.com

laura.sassi@verizon.net

janekelleybooks@gmail.com

Angela Burke Kunkel

Random House/Schwartz & Wade

Elementary

EST, hours flexible

https://www.angelakunkel.com

ang.kunkel@gmail.com

Bea Birdsong

Macmillan

Elementary

EST 10:30 AM to 2:30 PM

www.beabirdsong.com

beabirdsong@gmail.com

Carol Gordon Ekster

Boulder, Mazo, Pauline Books and Media, Clavis, Beaming Books

Elementary

EST 12:00-3:00

Https://carolgordonekster.com

Cekster@aol.com

Saira Mir

Simon and Schuster

Elementary

Eastern 10 am – 2 pm

Sairamir.com

Contact@sairamir.com

Vicky Fang

Scholastic, Sterling

Elementary

9:30am-2:00pm PST

Vickyfang.com

vicky.fang@gmail.com

Mark Holtzen

Sasquatch Publishing/Little Bigfoot

Elementary

Pacific/9am-12pm

www.markholtzen.com

holtzy@markholtzen.com

Varsha Bajaj

Nancy Paulsen Books, Penguin Group

Elementary

Central time. Live in Houston. Between 10 am and noon

Www.Varshabajaj.com

Author@varshabajaj.com

Sharon Langley

Abrams

Elementary

Pacific (West Coast) 11:30 – 12:30, 12:00-1:00, 3:00-4:30

www.sharonlangley.com

sharonelangley@gmail.com

Kathleen Blasi

Sterling Children’s Books

Elementary

EST 9AM-2PM

www.kmblasi.com

Kathy@kmblasi.com

Shelley Johannes

Disney Hyperion

Elementary

EST 9:30-2:00

www.shelleyjohannes.com

Shelley_Johannes@yahoo.com

Jen Calonita

Sourcebooks, Disney

Elementary

EST between 9AM and 3PM

www.jencalonitaonline.com

jenLsmith1971@gmail.com

Patricia Bailey

Albert Whitman and Company

Elementary

Pacific 9:30 – 3:00

www.patriciabaileyauthor.com

patriciabaileyauthor@gmail.com

Nancy Tupper Ling

Penguin

Elementary

EST 9-2

Www.nancytupperling.com

nancytupperling@gmail.com

Dianne White

Beach Lane/S&S; HMH

Elementary

6:30 am – 2:00 pm MST

https://diannewrites.com

diannewrites@gmail.com

Veronica Bartles

Balzer + Bray / Harper Collins

Elementary

Eastern – 8am-3:30pm

http://vbartles.com

vbartleswrites@vbartles.com

Lori Degman

Sterling Publishing, Sleeping Bear Press, Creston Books, Simon & Schuster

Elementary

8:00 AM – 5:00 PM CST

www.Loridegman.com

Lori@Loridegman.com

DuEwa Frazier

Lit Noire Publishing Children

Elementary

CST 9am – 4pm

www.duewaworld.com

duewa@duewaworld.com

Naomi Milliner

Running Press

Elementary

Eastern Standard 9-5

WordPress.com Naomi milliner

Naomiwm@verizon.net

Elizabeth Bluemle

Candlewick Press

Elementary

EST 8-3

www.elizabethbluemle.com

ehbluemle@gmail.com

Karlin Gray

Sleeping Bear Press

Elementary

East Coast; mornings 9-11

karlingray.com

Karlingray@me.com

Shannon Anderson

Free Spirit Publishing

Elementary

Central Standard Time, Available 11:00, 1:10, 3:10

www.shannonisteaching.com

shannonisteaching@gmail.com

Jonathan Rosen

Skyhorse Publishing

Elementary

8-4 EST

www.Houseofrosen.com

Houseofrosen@aol.com

Yvonne Pearson

Minnesota Historical Press

Elementary

Central, 9:00 am – 3:00 pm

www.yvonnepearson.com

yepearson@gmail.com

Gita Varadarajan

Scholastic

Elementary

EST- 10:50- 11:40a.m. and 11:50a.m. – 12:20p.m.

gitavarad@gmail.com

Karen Leggett Abouraya

Lee & Low

Elementary

Eastern – 7am – 7 pm

Handsaroundthelibrary.com

Karen@handsaroundthelibrary.com

Courtney Pippin-Mathur

Flashlight Press, Simon & Schuster (Little Simon)

Elementary

EST Between 9am-1pm

www.pippinmathur.com

courtney@pippinmathur.com

Beth Anderson

S&S, Calkins Creek

Elementary

8am-4pm MST

bethandersonwriter.com

beth@bethandersonwriter.com

Megan Wagner Lloyd

Knopf/Random House and Simon and Schuster

Elementary

EST 9 am to 2 pm

meganwagnerlloyd.com

meg@meganwagnerlloyd.com

Helen Perelman

Simon and Schuster

Elementary

EST 8:30-2:30

www.Helenperelman.com

Helen@helenperelman.com

Oge Mora

Little, Brown

Elementary

10am to 2pm ET

http://www.ogemora.com/

ogemora@gmail.com

Margo Sorenson

Pelican Publishing, Marimba/Just Us Books, Perfection Learning, Fitzroy Books

Elementary

Pacific Time, available from 6:30 AM to 4:30 PM

www.margosorenson.com

ms@margosorenson.com

Laura Roettiger

Eifrig Publishing

Elementary

MT 9am – 1pm

https://lauraroettigerbooks.com/

Ljrwritenow@gmail.com

Brenda Maier

Scholastic, Simon & Schuster

Elementary

9-9:45 am central time

BrendaMaier.com

Bmaierauthor@gmail.com

Corinne Demas

Scholastic, Hyperion/Disney etc.

Elementary

EST 9a.m.–3p.m.

www.corinnedemas.com

writer@corinnedemas.com

Sherry Howard

Clear Fork, Rourke, Teacher Created Materials

Elementary

Eastern, Eastern Time 10AM through 7PM

www.sherryhowardwritesforkids.com

sherryhoward0@icloud.com

Deborah Kalb

Schiffer

Elementary

Eastern. 9-11am, 1:30-3pm

deborahkalb.com

deborahkalb@yahoo.com

Gabrielle Balkan

Phaidon

Elementary

Eastern Standard Time between 10 am – 3pm

www.gabriellebalkan.com

gabrielle.s.balkan@gmail.com

Michelle Schaub

Charlesbridge

Elementary

Central. 9am-3pm

http://www.michelleschaub.com/

shellschaub@hotmail.com

Andrew Katz

CrackBoom! Books / Chouette

Elementary

EST (Montreal) / anytime except Tues or Thur after 4 pm

andrewkatzbooks.ca

akatz@dawsoncollege.qc.ca

Elizabeth Steinglass

Boyds Mills & Kane

Elementary

EST 8:30-10:30am

www.ElizabethSteinglass.com

Liz.Steinglass@gmail.com

Gretchen McLellan

Peachtree, Holiday House, Knopf, Little Bee, Beach Lane

Elementary

PST 9 am -3 pm

gretchenmclellan.com

gretchenmclellan@comcast.net

Susannah Buhrman-Deever

Candlewick Press

Elementary

EST 9:30 am—1 pm

buhrmandeever.com

susannahbdeever@gmail.com

Jennifer Gennari

HMH and Simon & Schuster (2020)

Elementary

PST (CA) available 8 am to noon

https://www.jengennari.com/

jengennari@gmail.com

Wendy Greenley

Creative Editions

Elementary

9-12 EST

www.wendygreenley.com

wgreenley@comcast.net

Arianne Costner

Random House Children’s Books

Elementary

Pacific time, Any day from 8-2

https://ariannecostner.wordpress.com/

ariannecostner@gmail.com

April Jones Prince

Holiday House, Macmillan, Scholastic, Penguin Random House, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Elementary

9am – 3 pm EST

www.apriljonesprince.com

april@apriljonesprince.co

Joyce Wan

FSG/Macmillan, Scholastic, Beach Lane Books/S&S

Elementary

10am-3pm EST

http://www.wanart.com

joyce@wanart.com

Wendy BooydeGraaff

Ripple Grove Press

Elementary

Eastern, 1 PM – 4 PM

https://www.wendybooydegraaff.com

https://www.wendybooydegraaff.com/contact-form

Abraham Schroeder

Ripple Grove Press

Elementary

9-12 PST, may have a few slots in the afternoon

http://www.TheGentlemanBat.com

abraham@thegentlemanbat.com

Keila Dawson

Pelican Publishing & Charlesbridge Publishing

Elementary

EST

www.keiladawson.com

keilavdawson@gmail.com

Stephanie Robinson

Random House

Elementary

EST 8:30-1:15

www.fairdaysfiles.com

robinsonstef@yahoo.com

Josephine Cameron

Macmillan/FSG Books for Young Readers

Elementary

EST 9:00-2:30 (updated availability listed on my website)

https://josephinecameron.com

josie@josephinecameron.com

Baptiste Paul

North South Books, Lerner, Little Bee.

Elementary

CST (Central Time Zone)

www.baptistepaul.net

litbybp@gmail.com

Adeola Eze

Jordan Hill Books

Elementary

West Central Africa – 10:00 hours

www.jordanhill.org

adeola.eze@jordanhill.org

Jenny Sue Kostecki-Shaw

Christy Ottaviano Books/Henry Holt

Elementary

Mountain-Denver, 8am – 11:30am

jennysuekosteckishaw.com

coloredsock@mac.com

K. Ali

Little Brown (for picture book THE PROUDEST BLUE)

Elementary

EST 9 am to 3 pm

skalibooks.com

skalibooks@gmail.com

Amy E. Sklansky

Scholastic, HaprerCollins, Quarto, Little Brown

Elementary

8:00 – 10:30am CST

www.amysklansky.com

sklanskys@att.net

Nanci Turner Steveson

HarperCollins

Middle School

Mountain time. 7:30am to 2:30pm

www.nanciturnersteveson.com

ponywriter7@gmail.com

FOR MIDDLE SCHOOL READERS

Jenn Bishop

Aladdin/Simon & Schuster and Knopf/Penguin Random House

Middle School

10-4 PM Eastern

http://www.jennbishop.com

jenn@jennbishop.com

Dee Garretson

Macmillan

Middle School

Eastern 8:00 AM to 5: PM

deegarretson.com

deegarretson@gmail.com

Jennifer Swanson

Peachtree Publishers

Middle School

EST, from 10am to 3pm

www.jenniferSwansonbooks.com

jennifer@jenniferswansonbooks.com

Gail D. Villanueva

Scholastic

Middle School

I’m in Manila Standard Time but I can do 9AM to 1PM Eastern Time

https://gaildvillanueva.com

gaildvillanueva@gmail.com

Amalie Jahn

Light Messages

Middle School

EST – flexible hours

www.amaliejahn.com

amaliejahn@gmail.com

Melissa Sarno

Knopf Books for Young Readers

Middle School

9am-2pm EST

melissasarno.com

melissa.sarno@gmail.com

Beth McMullen

Simon & Schuster/Aladdin

Middle School

PST 9:00-3:00

BethMcMullenBooks.com

bethvamcmullen@gmail.com

Chris Tebbetts

Jimmy Patterson; Penguin-Puffin; Delacorte

Middle School

EST; anytime 8AM-8PM

www.christebbetts.com

tebbetts.chris@gmail.com

- Anderson Coats

Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Middle School

PST – available 10:00-3:00

https://www.jandersoncoats.com/

jandersoncoats at gmail dot com

Melanie Sumrow

Yellow Jacket/S&S

Middle School

CST (9:00am-2:00pm)

www.melaniesumrow.com

melanie@melaniesumrow.com

Kip Wilson

HMH Versify

Middle School

EST between 8am and 1pm

http://www.kipwilsonwrites.com/

kiperoo@gmail.com

Emma Otheguy

Knopf Books for Young Readers, Lee & Low Books, and others

Middle School

EST 8am-3pm

www.emmaotheguy.com

emma.otheguy@gmail.com

Cindy Baldwin

HarperCollins

Middle School

Pacific time zone; 9am-1:30pm PST

www.cindybaldwinbooks.com

cindybaldwinbooks@gmail.com

Nancy Castaldo

HMH, Quarto, DK, Nat Geo

Middle School

EST, 9 am – 12 pm

www.nancycastaldo.com

nancycastaldo@nancycastaldo.com

Paula Chase

HarperCollins/Greenwillow

Middle School

Eastern Standard 10 am – 12 noon

paulachasebooks.com

paulachy@gmail.com

Nicole Melleby

Algonquin Young Readers

Middle School

EST – All day

www.nicolemelleby.com

nicole@nicolemelleby.com

Sarah McGuire

Lerner

Middle School

EST, after 1:30 PM

sarahmcguirebooks.com

smguire.author@gmail.com

Nicole Valentine

Lerner/Carolrhoda

Middle School

Eastern – 9-4pm

www.nicolevalentinebooks.com

nicole@valentines.net

Fran Wilde

Abrams / Amulet

Middle School

EST 10am-3pm

Franwilde.net

online.wilde@gmail.com

Lee Gjertsen Malone

Aladdin/S&S

Middle School

EST 8am to 4pm

Leegjertsenmalone.com

Leegjertsenmalone@gmail.com

Janae Marks

HarperCollins (Katherine Tegen Books)

Middle School

Eastern time. Between 9 am – 5 pm.

www.janaemarks.com

janaemarksbooks@gmail.com

Lindsay Currie

Simon & Schuster, Sourcebooks

Middle School

I’m on central time. Available to Skype between 9-2.

www.lindsaycurrie.com

lindsayncurrie@gmail.com

Rajani LaRocca

Yellow Jacket/Little Bee Books

Middle School

Eastern, 8 am – 8 pm

www.rajanilarocca.com

rajani.larocca@gmail.com

Ann Braden

Skyhorse Publishing

Middle School

EST 10:30am – 12:00 and 12:30pm- 2:30pm

annbradenbooks.com

annbbraden@gmail.com

Rebecca Rupp

Candlewick

Middle School

8 AM – 4 PM EST

www.rebeccaruppresources.com

rebeccarupp@gmail.com

Malayna Evans

Month9Booka

Middle School

cst, 9a-4p

Malaynaevans.com

Malaynaevans22@gmail.com

Jessie Janowitz

Sourcebooks

Middle School

EST 9:30-2:30

Jessiejanowitz@gmail.com

Jejanowitz@gmail.com

Irene Latham

Lerner Publishing

Middle School

9-2 cst

www. irenelatham.con

irene@irenelatham.com

Deborah Heiligman

Macmillan

Middle School

EST from 11:00am-6:00pm most days

www.DeborahHeiligman.com

Deborah@DeborahHeiligman.com

Brooks Benjamin

Random House

Middle School

EST 8:00 am – 4:00 pm

www.brooksbenjamin.com

cbrooksbenjamin@gmail.com

Amy Cherrix

Houghton Mifflin Books for Young Readers

Middle School

EST from 9a-11a

www.amycherrix.com

acherrix@me.com

Jennifer Camiccia

Aladdin/Simon&Schuster

Middle School

Anytime between 8:15 to 1:00 PST

Jencamiccia.com

jencamiccia@gmail.com

Alyson Gerber

Scholastic

Middle School

10am-12pm

AlysonGerber.com

Alyson@alysongerber.com

Dan Haring

Sourcebooks

Middle School

Mountain – 8AM-5PM

https://danharingart.com/

danharing@gmail.com

Mike Hays

Writer’s Digest Books, Month9Books

Middle School

Central 8:30-11:30

www.mikehaysbooks.com

coachhays@gmail.com

Kathleen Burkinshaw

Simon and Schuster and Scholastic

Middle School

EST and from 9:30amEST – 3pm EST

www.kathleenburkinshaw.com

klburkinshaw@gmail.com

Laurie Morrison

Abrams

Middle School

9:00-11:00 am EST, 2:00-4:00 pm EST

lauriemorrisonwrites.com

lauriemorrisonwrites@gmail.com

Alison Pearce Stevens

National Geographic Kids Books

Middle School

Central Time, available 9:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m.

http://apstevens.com/

alison@apstevens.com

Sylv Chiang

Annick Press

Middle School

Eastern Standard (9:30-11:30 am)

sylvchiang.com

info@sylvchiang.com

S.A. Larsen

Ellysian Press

Middle School

EST – 9AM – 1:30PM

https://www.salarsenbooks.com/

sheri@salarsenbooks.com

Jackie Yeager

Amberjack Publishing

Middle School

EST 9:00am- 3:00pm

www.swirlandspark.com

jacquelineyeager5@gmail.com

Amy Makechnie

Simon and Schuster

Middle School

Eastern, anytime after 10:30am!

https://amymakechnie.com

amym@proctoracademy.org

Ginger Johnson

Bloomsbury

Middle School

Central European time zone 9:00 am EST—2:00 EST

Gingerjohnsonbooks.com

Ginger@gingerjohnsonbooks.com

Jen Petro-Roy

Macmillan/Feiwel & Friends

Middle School

EST, 9am-3pm

http://www.jenpetroroy.com

jpetroroy@gmail.com

Laura tucker

Viking Children’s

Middle School

EST. Available from 8am on!

Lauratuckerbooks.com

ltucker@gmail.com

Kristin Thorsness

Month9Books

Middle School

PST free from 9:30-1:00

kristinthorsness.com

kristin.thorsness@gmail.com

Joshua S. Levy

Lerner/Carolrhoda

Middle School

Eastern US time zone & any time.

www.joshuasimonlevy.com

joshlevywrites@gmail.com

Jeanne Zulick Ferruolo

Farrar Straus Giroux Book/Macmillan

Middle School

Eastern — any time

JZULFERR.COM

JZULFERR@GMAIL.COM

Samantha M Clark

Paula Wiseman Books/Simon & Schuster

Middle School

CST 8am to 3pm

http://www.samanthamclark.com/

samantha@samanthamclark.com

Adrianna Cuevas

Macmillan

Middle School

CST, any time

adriannacuevas.com

adriannatcuevas@gmail.com

DONNA GEPHART

Simon and Schuster Books for Young Readers; Delacorte Press (Penguin Random House); Holiday House

Middle School

EST/8:30 a.m. – 3:00 p.m.

www.donnagephart.com

dgephartwrites@gmail.com

Henry Lien

Holt/Macmillan

Middle School

Pacific (California), 8 am – 8 pm

Www.henrylien.com

Info@henrylien.com

Melanie Conklin

Disney-Hyperion

Middle School

9:00am-3:00pm EST

www.melanieconklin.com

melanie@melanieconklin.com

Dianne K. Salerni

Harper, Clarion, Holiday House, Sourcebooks

Middle School

EST 11 am – 5 pm

http://diannesalerni.com/

dksalerni@gmail.com

Shannon Hitchcock

Scholastic

Middle School

EST 9:00–2:00

www.shannonhitchcock.com

shannonhitchcock.com/contact

Lisa Williams Kline

Blue Crow Publishing

Middle School

Eastern Time Zone — any hours

www.lisawilliamskline.com

lisa.williams.kline@gmail.com

Sandra Warren

Arlie Enterprises

Middle School

Eastern Time Zone – anytime

www.arliebooks.com

sandra@arliebooks.com

Jennie Englund

MacMillan

Middle School

Pacific, ANY TIME

Facebook.com/jennieenglund71

Englundmeads@hotmail,com

S.A. Larsen

Ellysian Press

Middle School

9:00 AM – 1:00 PM EST

www.salarsenbooks.com

sheri@salarsenbooks.com

Susan Diamond Riley

The University of South Carolina Press

Middle School

Available 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. EST

susandiamondriley.com

sdiamondriley@gmail.com

elly swartz

FSG/Macmillan and Scholastic

Middle School

11am – 2pm EST

https://ellyswartz.com/

ellyswartz@outlook.com

Lissa Price

Random House Children’s Books

Middle School

PT 10am-10pm

lissaprice.com

lissapriceauthor@gmail.com

Rebecca Petruck

Abrams Amulet

Middle School

https://www.rebeccapetruck.com/

rebecca_petruck@yahoo.com

Mike Grosso

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Middle School

8AM-3PM CST

https://mikegrossoauthor.com

me@mikegrossoauthor.com

Nicole Valentine

Lerner/Carolrhoda

Middle School

EST 9am – 2pm

Nicolevalentinebooks.com

Nicole@valentines.net

Shari Simpson

Disney Hyperion

Middle School

10am to 2pm EST

www.sharisimpson.com

sharisimpsonwrites@gmail.com

Sheila M. Averbuch

Scholastic

Middle School

GMT available 5-6 pm and 9-11 am

http://www.sheilamaverbuch.com

mailme@sheilamaverbuch.com

Barbara Dee

Aladdin/S&S

Middle School

9-2 ET

Barbaradeebooks.com

Barbara@Barbaradeebooks.con

Bev Katz Rosenbaum

Orca Book Publishers

Middle School

EST, flexible availability

http://bevkatzrosenbaum.com/

bevrosenbaum@yahoo.ca

Kim Ventrella

Scholastic/HarperCollins

Middle School

CST, all day

http://kimventrella.com/

Dana Alison Levy

Delacorte/Penguin Random House

Middle School

EST 10-4

www.danaalisonlevy.com

dana@danaalisonlevy.com

e.E. Charlton-Trujillo

Candlewick Press

Middle School

Pacific. 8:30 am – 3:00 pm

www.bigdreamswrite.com

Atrisksummer@gmail.com

Cathleen Barnhart

HarperCollins

Middle School

Eastern. I’m available from 11 am- 3 pm

Cathleenbarnhart.com

Cath.barnhart25@gmail.com

Sarah Darer Littman

Scholastic Aladdin/S & S

Middle School

EST. 8-9am. 12-5pm

sarahdarerlittman.com

sarahdarerlittman@gmail.com

Bridget Hodder

MacMillan FSG

Middle School

EST 10:00 -4:00

www.BridgetHodder.com

BridgetHodder@yahoo.com

Jonathan Rosen

Skyhorse Publishing

Middle School

8-4 EST

www.Houseofrosen.com

Houseofrosen@aol.com

Heather Gale

Tundra Books

Middle School

9-11 AM EST and 2-4 PM EST

www.heathergale.net

writergale@gmail.com

Tamara Ellis Smith

Schwartz and Wade/Random House and Barefoot Books

Middle School

EST and pretty flexible

tamaraellissmith.com

tsesmith@gmavt.net

Gayle C Krause

Clear Fork Publishing

Middle School

Eastern 10:00 – 12:00 AM

www.gayleckrause.com

krausehousebooks@yahoo.com

Marie Miranda Cruz

Starscape, Tom Doherty & Associates, Macmillan

Middle School

Pacific/7-10 am

Cruzwrites.com

mariveecruz@yahoo.com

Rebecca Hirsch

Lerner

Middle School

Eastern Time Zone, 11 am to 2 pm

www.rebeccahirsch.com

rebeccahirsch@mac.com

Ryan Dalton

Lerner; North Star Editions

Middle School

Central time zone. I am very flexible with hours and should be available most of the day.

Www.ryandaltonwrites.com

ryandaltonwrites@gmail.com

Sarah R. Baughman

Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Middle School

9 a.m. – 12 p.m. EST

https://www.sarahrbaughman.com

serbaughman@gmail.com

Jordan Jacobs

Sourcebooks

Middle School

Pacific Time: 9-3:30

www.j-jacobs.com

jnjacobs@j-jacobs.com

Sarah Cannon

Feiwel and Friends/Macmillan

Middle School

EST, 9-3

sarahcannonbooks.com

saillenotsallie@gmail.com

Cynthia Levinson

Peachtree, Simon & Schuster

Middle School

CST, 9-12, 1-3

www.cynthialevinson.com

clevinson@austin.rr.com

Aimee Lucido

Versify

Middle School

PST 8-5

www.aimeelucido.com

Aimeellucido@gmail.com

Lindsay Lackey

Macmillan/Roaring Brook Press

Middle School

PST, any time after 10 am PST

Www.lindsaylackey.com

lindsay@lindsaylackey.com

Lisa Schmid

North Star Editions

Middle School

PST

www.lisalschmid.com

lisa.schmid@sbcglobal.net

FOR HIGH SCHOOL READERS

Dee Garretson

Macmillan

High School

Eastern 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM

deegarretson.com

deegarretson@gmail.com

Caroline T Patti

Month9Books

High School

8-5 PST

carolinetpatti.com

carolinepattibooks@yahoo.com

Olivia Hinebaugh

Macmillan/swoon reads

High School

Eastern, before 12:30

Oliviahinebaugh.com

Oliviahinebaugh@gmail.com

Keely Hutton

FSG/Macmillan

High School

EST – 8AM – 3PM

www.keelyhutton.com

khutton1@rochester.rr.com

Kristy Acevedo

North Star Editions/Jolly Fish Press

High School

EST; time is flexible

kristyacevedo.com

Kristyacebooks@gmail.com

Martha Brockenbrough

Macmillan

High School

Pacific, 9-3

marthabrockenbrough.com

martha@marthabee.com

Rebecca Sky

Hodder Children’s Book, Hachette UK

High School

GMT and I’m flexible

www.rebeccasky.com

authorrebeccasky@gmail.com

Carolyn O’Doherty

Boyds Mills & Kane

High School

Pacific 8:00 – 4:00

www.carolynodoherty.com

carolyn.odoherty.author@gmail.com

Vesper Stamper

Knopf

High School

EST, 9-11 am

vesperillustration.com

studio@vesperillustration.com

Kathryn Berla

Chicago Review Press /North Star Editions

High School

PST (11 AM to 5PM)

https://www.KathrynBerlaBooks.com

BerlaBooks@gmail.com

Christina June

Blink/HarperCollins

High School

EST 8 am – 5 pm

www.christinajune.com

Christinajuneya@gmail.com

Olivia Hinebaugh

Swoon Reads/Macmillan

High School

Eastern 9-12

Oliviahinebaugh.com

Oliviahinebaugh@gmail.com

Emily Anderson

West 44 Books

High School

Central Time Zone 11 a.m-5 pm

www.emily-anderson.net

anderson.emily.christine@gmail.com

I’ll be updating this list every few weeks until WRAD, so if you check back, you may find that the options will change. Schedules will fill, so some folks will no longer be available, but there will also be new people added.

Authors & Illustrators: If your schedule is full & you need to be crossed off the list, please leave a comment to let me know. Please note that this particular list is limited to traditionally published authors/illustrators (such as those listed here), only to limit its size and scope. I’m one person with limited time. However, if someone else would like to compile and share a list of self-published, specialty, magazine, and ebook author/illustrator volunteers, I think that would be absolutely great, and I’ll happily link to it here. Just let me know!

Happy reading, everyone!

~Kate

“World Read Aloud Day is about taking action to show the world that the right to read and write belongs to all people. World Read Aloud Day motivates children, teens, and adults worldwide to celebrate the power of words, especially those words that are shared from one person to another, and creates a community of readers advocating for every child’s right to a safe education and access to books and technology.” ~from the LitWorld website

When Mia moves to Vermont the summer after seventh grade, she’s recovering from the broken arm she got falling off a balance beam. And packed away in the moving boxes under her clothes and gymnastics trophies is a secret she’d rather forget.

When Mia moves to Vermont the summer after seventh grade, she’s recovering from the broken arm she got falling off a balance beam. And packed away in the moving boxes under her clothes and gymnastics trophies is a secret she’d rather forget.

Once I’ve written the last chapter, I’m ready to take a short break and then dive back in, fixing up those issues I’ve already identified. That becomes my first round of revision, and I’ll share some photos of what that looks like in my next post.

Once I’ve written the last chapter, I’m ready to take a short break and then dive back in, fixing up those issues I’ve already identified. That becomes my first round of revision, and I’ll share some photos of what that looks like in my next post.

When Mia moves to Vermont the summer after seventh grade, she’s recovering from the broken arm she got falling off a balance beam. And packed away in the moving boxes under her clothes and gymnastics trophies is a secret she’d rather forget.

When Mia moves to Vermont the summer after seventh grade, she’s recovering from the broken arm she got falling off a balance beam. And packed away in the moving boxes under her clothes and gymnastics trophies is a secret she’d rather forget.