Good morning and Happy Saturday! Today’s TW guest post is from Erin Hagar, the author of JULIA CHILD: AN EXTRAORDINARY LIFE IN WORDS AND PICTURES and AWESOME MINDS: THE INVENTORS OF LEGO TOYS. Erin’s joining us to talk about the power of play.

Let’s Play: Toys as (another) way into your character

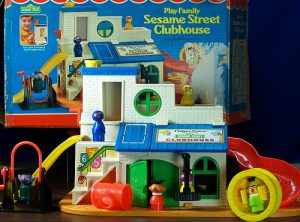

When I was a kid, this was my favorite toy: the Sesame Street Clubhouse.

I remember spending hours lying on the floor with my dad, helping Bert and Ernie and Grover go down the slide and through the chutes and around the merry-go-round. My dad found this toy on E-bay a couple of years ago, and my kids and their friends loved it, too.

But looking at this toy dredges up painful memories, too. When my parents divorced, they fought–a lot, loudly–about where this toy should live. When I see this toy in my adult home, all these years later, I feel a strange mix of emotions.

Some toys are just objects. Stuff. Easily donated to Goodwill when they’ve gathered dust. But others, like my Sesame Street clubhouse, are loaded with meaning and emotion. They can be loaded in our writing, too. Just as we use setting and dialogue to spotlight character and conflict, objects (and today I’ll focus on toys) can provide a window into our characters.

Sure, we could say a character is “competitive.” But wouldn’t it be better to show her marking the deck of Old Maid cards, like I used to do? Or stealing money from the Monopoly bank? We could label our character a “neatnik.” But what about a scene where he organizes his Lego collection by size and color? Or, even better, showing how he responds when his little sister barges into his room and dumps them all on the floor?

Another great thing about toys is that some of them come to us preloaded with universal associations. Dolls and stuffed animals can mean comfort. A shiny new two-wheeler means independence and freedom. But writers can turn these associations on their heads. Consider this, from Lois Lowry’s Newbery-award winning novel, The Giver:

Finally, the Nines were resettled in their seats, each having wheeled their bicycle outside where it would be waiting for its owner at the end of the day. Everyone always chuckled and made small jokes when the Nines rode home for the first time. “Want me to show you how to ride?” older friends would call, “I know you’ve never been on a bike before.” But invariably, the grinning Nines, who in technical violation of the rule had been practicing secretly for weeks, would mount and ride off in perfect balance, training wheels never touching the ground. (pg. 41)

Yes, bikes in the society Lowry’s created mean freedom and independence, just like in our word. But what does freedom mean when eight-year olds are technically forbidden to ride them?

Toys and play are universal aspects of childhood, but the specific ways your character plays and the specific toys she plays with (or played with, if she’s older) can tell us a lot about your character and the world she inhabits.

Now, let’s play!

Free write activity: Take a character from your WIP (any age) and think about a toy they might own or used to own. (The toy doesn’t have to be a part of the work right now, and don’t feel like you have to find a way to force it into your work. This is just an exercise to learn more about your character.) Free write about that toy, considering some of the following questions:

How did your character get the toy? Was it a gift? A hand-me-down? Did he find it? Steal it? How did the character feel about getting it? How does the character feel about the toy now?

What’s the toy made of? Is it plush? China? Wood? Plastic? How does it move? What condition is it in? Why? Where is it in the character’s room? Displayed in a protective plastic case? Stuffed in the bottom of the closet? Does anyone else want it? Does anyone make fun of it? Is it played with? Alone or with other characters? Under what conditions does your character most want to play with that toy?

Does the toy have a life of its own when the child is away? If the toy could speak, what would it say? What would be a memorable occasion in its life?

I’d love to hear if you had any new insights into your character from this exercise. Let me know in the comments!