It’s time for your Thursday Quick-Write with guest author Erin Dealey. Erin writes board books, picture books, mg, YA–and raps. : ) Her picture book, DECK THE WALLS (Sleeping Bear Press), a kid’s-eye view of holiday dinners, will release Sept. 21st. Erin is an English/ theater teacher, Area 3 Writing Project presenter (UCDavis), and heads the theater department at Sugarloaf Fine Arts Camp each summer. Former co-Regional Advisor for SCBWI CA North/Central, Erin has presented at conferences, reading association PDIs, and LOVES school visits. Today, she joins us to talk about…

It’s time for your Thursday Quick-Write with guest author Erin Dealey. Erin writes board books, picture books, mg, YA–and raps. : ) Her picture book, DECK THE WALLS (Sleeping Bear Press), a kid’s-eye view of holiday dinners, will release Sept. 21st. Erin is an English/ theater teacher, Area 3 Writing Project presenter (UCDavis), and heads the theater department at Sugarloaf Fine Arts Camp each summer. Former co-Regional Advisor for SCBWI CA North/Central, Erin has presented at conferences, reading association PDIs, and LOVES school visits. Today, she joins us to talk about…

Voice

Good Morning! Since it’s almost Back-to-School for all, I thought it would be a good time to share a lesson I have used in my classes–at many grade levels–so you can take it back with you. (Warning–it’s a bit longer than a “Mini” lesson–but it has truly resonated with my students.)

If you’ve been doing the quick-writes (and posting them) and/or keeping a Writer’s Notebook, as Kate suggested in June, chances are your own voice has evolved this summer. In fact, take a look at your first entries & posts and compare them to recent ones. (Go ahead–I’ll wait. Just don’t forget to come back…)

Notice any differences between your earlier entries and now? (Other than the luxurious feeling that summer stretched endlessly before you.) When I participated in my first Writer’s Project summer seminar, I remember making sure my writing was grammatically correct. After all, I taught English, right? The result was a textbook tone that had me zoning off by the end of the opening paragraph, a stark contrast to the plays and skits I’d written for my drama students.

Which brings us to voice.

I’ve heard many editors say voice is what hooks the reader. Even non-fiction needs an engaging voice. Some editors say you can teach form and plot, but you can’t teach voice. I disagree. The breakthrough for me came when I realized a big part of teaching theater is voice. Voice comes from learning who you are, and not being afraid to share that honesty with others. As you’ve grown more comfortable with your writing this summer, your own voice has emerged or grown stronger. However–as you’ve also experienced this summer, this sharing takes courage, even in this supportive community of TeachersWrite!

“To gain your own voice, you have to forget about having it heard.”

—Allen Ginsberg

If your students are like mine, voice takes tremendous courage. It emerges first in journals and quick-writes, and I always make a point to comment when a student’s voice shows up on the page. Like this acrostic I got from Darin A. , one of my seniors who bristled at any assignment from an authority figure…

Darin

Ain’t

Really

Into

No

Acrostics.

The day I used it as an excellent example of voice, Darin’s writing took off. Voice freed him to see writing and words as power–not just a means to complete his assignment.

But it’s scary. Even for adults.

When my writing pal, debut author Scott Blagden wrote the first drafts of his YA novel, DEAR LIFE YOU SUCK, he was afraid publishers would reject it because of the profanity used by his main character, Cricket, so Blagden tried to make his character’s voice softer.

“I toned down a lot of the language, the swear words,” Scott explains; “I toned down some of the jokes and this and that, and then I read the whole book and I had lost the character. I had lost the voice.”

Voice and vocabulary, sentence structure & pace (long sentences or short choppy ones &/or fragments) grow from your character–or the character of your narrator.

One way to release student voices is by warming up with a stream-of-consciousness format I call Clearing out the Cobwebs. (The following is what I tell my students. Try it!)

Clearing the Cobwebs. When I say “Go”, write 3 words per line (stream of consciousness—not laundry or grocery list…) until your are told to stop. (usually 3-5 minutes) If your mind is blank, start with I don’t know what to write, or a line from your favorite song. If you get stuck on a word, DON’T STOP WRITING Write your last word word word over and over until something clicks. Don’t think—WRITE !The cool thing about this Cobweb pre-write exercise is that students think it’s so ridiculous, they let go of trying to write, and their authentic voice emerges.

Another way to approach voice is to refer to it as eavesdropping. Creating the voice of a character is easier if you think of it like acting in the theater: Being someone else for a while. If you ask my students, they’ll probably tell you my Best Rule Ever is: Stop thinking–and listen.

In DEAR LIFE, Blagden learned to listen, by “getting into character,” along the same lines as actors do. “When I would sit down at the computer,” he says, “I would get into character, and start writing in his voice. I wasn’t just writing about the character, I was [the] character.”

The voice of my latest picture book, DECK THE WALLS, came easily since I originally wrote it for my high school theater students to perform at a holiday assembly, and I could hear their voices.

Read the first 2 pages of any of the following books aloud and LISTEN to each voice. {Some of the books are on your summer Suggested Reading list. If you don’t have copies of these yet, you can find their first pages on Amazon –after which I bet you’ll want to read the whole book!}

Note that it’s not just the tone of the reader that distinguishes each voice. Patterns, pace, word choice, pet phrases, and content/topics make each voice different. Each first page is like meeting a different person. What makes each voice stand out?

First person:

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain (Remember when we used to call “voice” = “writing in the vernacular” ?)

Locomotion, Jacqueline Woodson http://www.jacquelinewoodson.com/

The One and Only Ivan, Katherine Applegate http://theoneandonlyivan.com/

Percy Jackson & the Olympians: the Lightening Thief , Rick Riordan http://www.rickriordan.com/home.aspx

Geronimo Stilton, The Curse of the Cheese Pyramid http://geronimostilton.com/portal/US/en/home/

Pickle, Kim Baker http://www.kimberlycbaker.com/KCB/Home.html

Pull of Gravity, Gae Polisner http://gaepolisner.com/html/ya.html

Dear Life You Suck, Scott Blagden http://scottblagden.com/

How does the tone of the YA’s differ from the middle grades novels above? What tips you off to the age of the protagonist/narrator?

Third person:

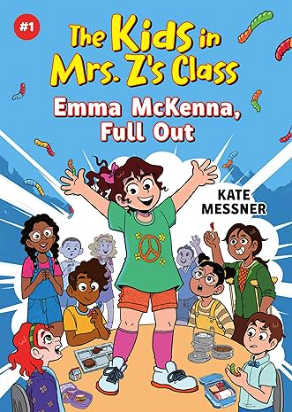

Hide and Seek, Kate Messner, https://katemessner.com/hide-and-seek/ How does the narrator set the tone? How does the grandmother’s voice (especially pg. 2) differ from the narrator?

Capture the Flag, Kate Messner https://katemessner.com/capture-the-flag/

“It ain’t whatcha write, it’s the way atcha write it.”

—Jack Kerouac

Now, do some eavesdropping of your own….

This lesson actually evolved when my husband asked why I have such a collection of “rusty, dusty” antiques. Now I use these treasures as writing prompts. : )

VOICES

In advance: select an object –anything will do–an antique, a child’s toy, family memento, etc.

Variation for your classroom: If you’re introducing a book or even a history unit to your class, gather some objects that might represent that story or era. I once used a few river rocks (the Acropolis) and my husband’s “Greek” sandals to intro a mythology unit.

What I tell my students: Each object, like a seashell which whispers of the ocean’s roar, has a unique story to tell. All you have to do is eavesdrop, and write it down.

The stories have been left on the object by all who have come in contact with it: The person who made it, the one who sold it, the one who purchased it, or trades for it, or received it as a gift; the person who tossed it in the attic, and the one who found it again… All of these people have left their stories for you to find.

No two individuals will hear the same story, because the object knows which one you want to hear.

DON’T THINK !!! (Students love this rule.) LISTEN !!!!!

(And write down what you hear…)

I can’t wait to read what you’ve HEARD!

Note from Kate: Me too! So please share a sample of today’s writing in the comments if you’d like.

On some level of course this is obvious; and it’s also true of any book, any genre. But I think in my case, when I began writing my YA science fiction novel PARADOX, I didn’t fully realize just how science intensive it would end up being. The story seed began in my mind with the main character, Ana, who awoke confined in a small room without any memories or knowledge of who or where she was. As the plot came together and the backstory unfolded, I quickly determined that the small space was the inside of a rocket; that Ana was on a far-off, habitable planet; and that she had an unknown mission to accomplish and a limited time to do so.

On some level of course this is obvious; and it’s also true of any book, any genre. But I think in my case, when I began writing my YA science fiction novel PARADOX, I didn’t fully realize just how science intensive it would end up being. The story seed began in my mind with the main character, Ana, who awoke confined in a small room without any memories or knowledge of who or where she was. As the plot came together and the backstory unfolded, I quickly determined that the small space was the inside of a rocket; that Ana was on a far-off, habitable planet; and that she had an unknown mission to accomplish and a limited time to do so. Good morning! It’s time for your Thursday Quick-Write, and we have a double dose for you today.

Good morning! It’s time for your Thursday Quick-Write, and we have a double dose for you today. Quick-Write option #2 comes from

Quick-Write option #2 comes from

Our guest author is

Our guest author is

Good morning! Our guest author for today’s quick-write is the lovely & talented

Good morning! Our guest author for today’s quick-write is the lovely & talented