Good morning! It’s Mini-Lesson Monday at Teachers Write. If you want to start with a warm-up, head on over to Jo’s blog, and then you can come back to today’s mini-lesson.

Our guest author today is Mara Rockliff, who joins us from Pennsylvania. She’s written many historical picture books, including Around America to Win the Vote (coming out August 2) and Mesmerized: How Ben Franklin Solved a Mystery that Baffled All of France. Mara is here today to talk about evaluating the reliability of research sources…

Research sources: whom can we trust?

Hey teachers and librarians! I’m so happy Kate invited me to hang out with you all today. So, I’ll just dive right in and say we’re living in a golden age for research. No matter what we’re interested in, it’s never been so quick and easy to find information. Of course, as we all know, it’s also never been so quick and easy to find information that is wrong!

Teaching students (and ourselves!) how to sift through all that information and decide which sources can be trusted is a daunting task. I mean, there’s basic good advice like “Don’t rely on Wikipedia”—unless you want to write about the Brazilian aardvark. But solid-looking sources can include serious errors, too.

Some researchers use the Two-Source Rule, which says, “If you’re not sure about a fact, look for a second source.” Over the years I’ve learned to add, “…and then it’ll turn out the first source used the second source, or they both got it from the same third source, so if it seems suspicious, keep digging till you figure out what’s going on!” (Okay, it may not be the snappiest rule, but it does help me avoid embarrassing mistakes.)

When I visit schools and talk to students about primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, I like to use the example of a game of Telephone or Whisper Down the Alley, where the information gets more and more garbled as it’s passed along. That’s why the boring-looking, small-print stuff at the back of a book—endnotes and bibliographies—are my favorite part. Why take someone else’s word if I can go back to the source?

But just because a source is primary, that doesn’t mean it can be trusted! When I researched Around America to Win the Vote, I found hundreds of articles printed in newspapers across the country between April and September of 1916. One of them said this:

This struck me as a little fishy. I knew that just driving cross-country was a really big adventure. There weren’t any road maps then. Sometimes there weren’t even any roads! Zigzagging to hit every state would certainly take longer than six months and much more than ten thousand miles.

So where DID they go? I went through all those articles and marked down each stop on a map. When a Philadelphia paper said “Yesterday the suffragists were here,” I put a green marker on Philadelphia. If it also said, “…and now they’ve left for Wilmington,” I put a yellow marker on Wilmington, Delaware. Then, when I found a Baltimore paper saying that the suffragists had just arrived from Wilmington, I could switch that yellow marker to a green one (since the stop had been confirmed) and add a green marker for Baltimore, too. And here’s what I found out about their route.

So, if primary sources can be wrong, and secondary sources can be wrong, and Wikipedia can be really, really wrong…whom can we trust?

We can trust ourselves—to research thoroughly, notice inconsistencies, use our common sense, and keep on digging till we’re satisfied. Let’s call it the “Tons of Sources Plus a Brain Rule.” Yeah, I know, that isn’t very snappy either. But it works!

Today’s assignment is a research challenge from Mara!

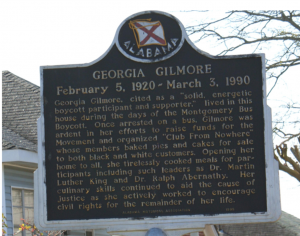

This historical marker stands outside Georgia Gilmore’s former home at 453 Dericote Street in Montgomery, Alabama. It contains three factual errors. The first person to find each error and post it in the comments will receive a signed book for your classroom, your choice of any of my books I have on hand. (I’ve got extras of all but one or two.) If all three errors haven’t been found by 9 p.m. Eastern time, I’ll tell you what they are. Cite your sources, please! 🙂

THE SEVENTH WISH is a story about wishes. I thought it would be fun to celebrate that theme at my book signings in Boston and Washington, D.C last month, so I asked people to share a wish on an index card. I promised to compile them into a community poem – and to take all of the index-card wishes home with me, to Lake Champlain, where THE SEVENTH WISH is set.

THE SEVENTH WISH is a story about wishes. I thought it would be fun to celebrate that theme at my book signings in Boston and Washington, D.C last month, so I asked people to share a wish on an index card. I promised to compile them into a community poem – and to take all of the index-card wishes home with me, to Lake Champlain, where THE SEVENTH WISH is set.